Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse. Follow us on twitter @cowboycoleridge. Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

well i thought i did

“But you didn’t”

oh no, did not know enough

to even get close

“You were a late bloomer”

yes, ignorant as a post

“But you learned

what matters”

with knowin’

comes the key –

one does not have to,

one just does

“Took us both a few tries”

and now lets do

© copyright 2023 mac tag/cowboycoleridge all rights reserved

quenched not, we behold in mutual arch, the first buds, witness arise, enkindled to what matters, by the kiss of need that blows, calls, our hands blossom where we touch, lips breathe, relent; feel not the frost’s flame parch; for this that consumes not but feeds the heart

© copyright 2022 mac tag/cowboycoleridge all rights reserved

to not, and do

it is how to exist

how else to be here

moments come

remembered

minds converge

life itself, grasped

that is how

those who know git by

they catch the changes

keep growin’

stimulatin’

so long as we persist

look back and see

that will be us

ridin’ the waves

© copyright 2021 mac tag/cowboycoleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

to not,

is to not exist

how else to be here

moments pass

forgotten

mood gone

life itself, gone

that is how

those who know git by

they catch the changes

keep growin’

stimulatin’

so long as we persist

look back and see

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

my lips burn, grief glows

a waltz over to the abyss

dark filled; the soul knows

that spring will not

matter …

never tire of waitin’

no time for worryin’

have been such

from the beginnin’

not even knowin’

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboycoleridge all rights reserved

sorry,

for all of the agony

and not enough ecstasy

i am sorry

means not much now,

but i am

i tried

at least, i think i did

whether you will agree with that,

i do not know

to not be weak, to be honest,

to not be scared, to do right,

to love, to be loved

i tried

you know, in each way,

whether i succeeded

i expect not

and i am sorry

it is inexcusable,

i need not be told that

how it took so long

to figure that out,

hell if i know

i had hoped for more

for you, for us

i miss you

i am sorry

© copyright 2017 mac tag/cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

On this day in 1842 – Giuseppe Verdi’s third opera, Nabucco, receives its première performance in Milan.

Costume sketch for Nabucco for the original production

|

|

Nabucco (short for Nabucodonosor, English Nebuchadnezzar) is an Italian-language opera in four acts composed by Verdi to an Italian libretto by Temistocle Solera. The libretto is based on biblical stories from the Book of Jeremiah and the Book of Daniel and the 1836 play by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois and Francis Cornue. The opera was first performed under its original name of Nabucodonosor.

Nabucco is the opera which is considered to have permanently established Verdi’s reputation as a composer. He commented that “this is the opera with which my artistic career really begins. And though I had many difficulties to fight against, it is certain that Nabucco was born under a lucky star”.

It follows the plight of the Jews as they are assaulted, conquered and subsequently exiled from their homeland by the Babylonian King Nabucco (in English, Nebuchadnezzar II). The historical events are used as background for a romantic and political plot. Perhaps the best-known number from the opera is the “Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves”, Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate / “Fly, thought, on golden wings”, a chorus which is regularly given an encore in many opera houses when performed today.

Synopsis

- Time: 587 BC

- Place: Jerusalem and Babylon

Act 1: Jerusalem

- ‘Thus saith the Lord, Behold, I shall deliver this city into the hand of the King of Babylon, and he will burn it with fire’ (Jeremiah 21:10)

Interior of the Temple of Solomon

The Israelites pray as the Babylonian army advances on their city (Gli arredi festivi giù cadano infranti / “Throw down and destroy all festive decorations”). The High Priest Zaccaria tells the people not to despair but to trust in God (D’Egitto là su i lidi / “On the shores of Egypt He saved the life of Moses”). The presence of a hostage, Fenena, younger daughter of Nabucco, King of Babylon, may yet secure peace (Come notte a sol fulgente / “Like darkness before the sun”). Zaccaria entrusts Fenena to Ismaele, nephew of the King of Jerusalem and a former envoy to Babylon. Left alone, Fenena and Ismaele recall how they fell in love when Ismaele was held prisoner by the Babylonians, and how Fenena helped him to escape to Israel. Nabucco’s supposed elder daughter, Abigaille, enters the temple with Babylonian soldiers in disguise. She, too, loves Ismaele. Discovering the lovers, she threatens Ismaele: if he does not give up Fenena, Abigaille will accuse her of treason. If Ismaele returns Abigaille’s love, however, Abigaille will petition Nabucco on the Israelites’ behalf. Ismaele tells Abigaille that he cannot love her and she vows revenge. Nabucco enters with his warriors (Viva Nabucco / “Long live Nabucco”). Zaccaria defies him, threatening to kill Fenena if Nabucco attacks the temple. Ismaele intervenes to save Fenena, which removes any impediment from Nabucco destroying the temple. He orders this, while Zaccaria and the Israelites curse Ismaele as a traitor.

Act 2: The Impious One

- ‘Behold, the whirlwind of the Lord goeth forth, it shall fall upon the head of the wicked’ (Jeremiah 30:23)

Scene 1: Royal apartments in Babylon

Nabucco has appointed Fenena regent and guardian of the Israelite prisoners, while he continues the battle against the Israelites. Abigaille has discovered a document that proves she is not Nabucco’s real daughter, but the daughter of slaves. She reflects bitterly on Nabucco’s refusal to allow her to play a role in the war with the Israelites and recalls past happiness (Anch’io dischiuso un giorno / “I too once opened my heart to happiness”). The High Priest of Bel informs Abigaille that Fenena has released the Israelite captives. He plans for Abigaille to become ruler of Babylon, and with this intention has spread the rumour that Nabucco has died in battle. Abigaille determines to seize the throne (Salgo già del trono aurato / “I already ascend the [bloodstained] seat of the golden throne”).

Scene 2: A room in the palace

Zaccaria reads over the Tablets of Law (Vieni, o Levita / “Come, oh Levite! [Bring me the tables of the law]”), then goes to summon Fenena. A group of Levites accuse Ismaele of treachery. Zaccaria returns with Fenena and his sister Anna. Anna tells the Levites that Fenena has converted to Judaism, and urges them to forgive Ismaele. Abdallo, a soldier, announces the death of Nabucco and warns of the rebellion instigated by Abigaille. Abigaille enters with the High Priest of Bel and demands the crown from Fenena. Unexpectedly, Nabucco himself enters; pushing through the crowd, he seizes the crown and declares himself not only king of the Babylonians but also their god. The high priest Zaccaria curses him and warns of divine vengeance; an incensed Nabucco in turn orders the death of the Israelites. Fenena reveals to him that she has embraced the Jewish religion and will share the Israelites’ fate. Nabucco is furious and repeats his conviction that he is now divine (Non son più re, son dio / “I am no longer King! I am God!”). There is a crash of thunder and Nabucco promptly loses his senses. The crown falls from his head and is picked up by Abigaille, who pronounces herself ruler of the Babylonians.

Act 3: The Prophecy

- ‘Therefore the wild beasts of the desert with the wild beasts of the islands shall dwell there, and the owls shall dwell therein’. (Jeremiah 50:39)

Scene 1: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Abigaille is now Queen of Babylon. The High Priest of Bel presents her with the death warrant for the Israelites, as well as for Fenena. Nabucco, still insane, tries to reclaim the throne without success. Though his consent to the death warrant is no longer necessary, Abigaille tricks him into signing it. When Nabucco learns that he has consigned his (true) daughter to death, he is overcome with grief and anger. He tells Abigaille that he is not in fact her father and searches for the document evidencing her true origins as a slave. Abigaille mocks him, produces the document and tears it up. Realizing his powerlessness, Nabucco pleads for Fenena’s life (Oh di qual onta aggravasi questo mio crin canuto / “Oh, what shame must my old head suffer”). Abigaille is unmoved and orders Nabucco to leave her.

Scene 2: The banks of the River Euphrates

The Israelites long for their homeland (Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate / “Fly, thought, on golden wings; [Fly and settle on the slopes and hills]”). The high priest Zaccaria once again exhorts them to have faith: God will destroy Babylon. The Israelites are inspired by his words.

Act 4: The Broken Idol

- ‘Bel is confounded, Merodach is broken pieces; her idols are confounded, her images are broken in pieces.’ (Jeremiah 50:2)

Scene 1: The royal apartments, Babylon

Nabucco awakens, still confused and raving. He sees Fenena in chains being taken to her death. In despair, he prays to the God of the Hebrews. He asks for forgiveness, and promises to rebuild the temple in Jerusalem and convert to Judaism if his prayers are answered (Dio di Giuda / “God of Judah! [The altar, your sacred Temple, shall rise again]”). Miraculously, his strength and reason are immediately restored. Abdallo and loyal soldiers enter to release him. Nabucco resolves to rescue Fenena and the Israelites as well as to punish the traitors.

Scene 2: The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Fenena and the Israelite prisoners are led in to be sacrificed (Va! La palma del martirio / “Go, win the palm of martyrdom”). Fenena serenely prepares for death. Nabucco rushes in with Abdallo and other soldiers. He declares that he will rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem and worship the God of the Israelites, ordering the destruction of the idol of Bel. At his word, the idol falls to the ground of its own accord and shatters into pieces. Nabucco tells the Israelites that they are now free and all join in praise of Jehovah. Zaccaria proclaims Nabucco the servant of God and king of kings. Abigaille enters, supported by soldiers. She has poisoned herself. She begs forgiveness of Fenena, prays for God’s mercy and dies.

| Tom Roberts | |

|---|---|

Roberts, c. 1895

|

|

Today is the birthday of Thomas William “Tom” Roberts (Dorchester, Dorset, England 8 March 1856 – 14 September 1931 Kallista); artist and a key member of the Heidelberg School, also known as Australian Impressionism. After attending art schools in Melbourne, he left for Europe in 1881 to further his training, and returned home in 1885, “primed with whatever was the latest in art”. He did much to promote en plein air painting and encouraged other artists to capture the national life of Australia. While he is best known for his “national narratives”, among them Shearing the Rams (1890), A break away! (1891) and Bailed Up (1895), he also achieved renown as a portraitist.

In 1896 he married 35-year-old Elizabeth (Lillie) Williamson. Many of his most famous paintings come from this period. Elizabeth died in January 1928, and Roberts remarried, to Jean Boyes, in August 1928. He died in 1931 of cancer in Kallista near Melbourne. He is buried near Longford, Tasmania.

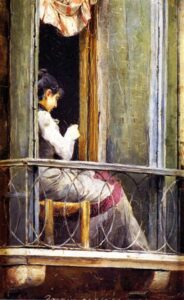

Gallery

The elusive louisa

Woman on a balcony

Adagio

-

Bourke Street, 1886, National Gallery of Australia

-

Coming South, 1886, National Gallery of Victoria

-

Slumbering Sea, Mentone, 1887, National Gallery of Victoria

-

A break away!, 1891, Art Gallery of South Australia

-

Bailed Up, 1895, Art Gallery of New South Wales

-

An autumn morning, Milson’s Point, Sydney, 1888, Art Gallery of New South Wales

-

Portrait of Florence, 1898, Art Gallery of New South Wales

| The Hon. Vita Sackville-West Lady Nicolson |

|

|---|---|

Vita Sackville-West by Philip de László, 1910

|

|

Today is the birthday of Victoria Mary Sackville-West, Lady Nicolson (Knole House, Kent 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962 Sissinghurst Castle, Kent), usually known as Vita Sackville-West,; poet, novelist, and garden designer. A successful and prolific novelist, poet, and journalist during her lifetime—she was twice awarded the Hawthornden Prize for Imaginative Literature: in 1927 for her pastoral epic, The Land, and in 1933 for her Collected Poems. She is remembered for the celebrated garden at Sissinghurst she created with her diplomat husband, Sir Harold Nicolson. Perhaps best remembered as the inspiration for the androgynous protagonist of the historical romp Orlando: A Biography, by her famous friend and admirer, Virginia Woolf, with whom she had a decade-long affair.

Vita’s first close friend was Rosamund Grosvenor (5 September 1888 – 30 June 1944), who was four years her senior. She was the daughter of Algernon Henry Grosvenor (1864–1907), and the granddaughter of Robert Grosvenor, 1st Baron Ebury. Vita met Rosamund at Miss Woolf’s school in 1899, when Rosamund had been invited to cheer Vita up while her father was fighting in the Second Boer War. Rosamund and Vita later shared a governess for their morning lessons. As they grew up together, Vita fell in love with Rosamund, whom she called ‘Roddie’ or ‘Rose’ or ‘the Rubens lady’. Rosamund, in turn, was besotted with Vita. “Oh, I dare say I realized vaguely that I had no business to sleep with Rosamund, and I should certainly never have allowed anyone to find it out,” she admits in her journal, but she saw no real conflict: “I really was innocent.”

Sackville-West was more deeply involved with Violet Trefusis, daughter of the Hon. George Keppel and his wife, Alice Keppel, a mistress of King Edward VII. They first met when Vita Sackville-West was 12 and Violet was 10, and attended school together for a number of years. The relationship began when they were both in their teens and strongly influenced them for years. Both later married and became writers.

In 1913, at age 21, Vita married the 27-year-old writer and politician Harold George Nicolson (21 November 1886 – 1 May 1968) in the private chapel at Knole. Nicknamed Hadji, or pilgrim, by his father, he was the third son of British diplomat Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock (1849–1928). The couple had an open marriage. Both Sackville-West and her husband had same-sex relationships before and during their marriage, as did some of the people in the Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists, with many of whom they had connections. Writing in the third person Sackville-West wrote in her early years of her marriage she “never knew the physical passion she had felt for Rosamund, she didn’t really miss it either”. Sackville-West saw herself as psychologically divided into two-one side of her personality was feminine, soft, submissive and attracted to men while the other side was masculine, hard, aggressive and attracted to women. Following the pattern of his father’s career, Harold Nicholson was at different times a diplomat, journalist, broadcaster, Member of Parliament, and author of biographies and novels. The couple lived from 1912 to 1914 in Cihangir, a suburb of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman empire and they returned to England in 1914 and bought Long Barn in Kent, where they lived from 1915 to 1930.

Vita and Trefusis eloped several times from 1918 on, mostly to France. While there Sackville-West dressed as a man when they went out together. The affair ended badly. Both families were concerned that the women were creating scandal. Trefusis continued to pursue Sackville-West to great lengths until Sackville-West’s affairs with other women finally took their toll. The two women apparently made a bond to remain faithful to one another, meaning that although both were married, neither could engage in sexual relations with her own husband. Sackville-West, who already had two children by Nicholson, was prompted to end the affair when she heard allegations that Trefusis had been involved sexually with her own husband, indicating that she had broken their bond. Despite the rift, the two women were devoted to one another, and deeply in love. They continued to have occasional liaisons for a number of years afterwards, but never rekindled the affair.

The affair for which Sackville-West is most remembered was in the late 1920s with the prominent writer Virginia Woolf. Woolf wrote about meeting Sackville-West that:

“Vita shines in the grocer’s shop in Sevenoaks…pink growing, grape clustered, pearl hung…There is her maturity and full-breastedness; her being so much full in sail on the high tides, where I am coasting down backwaters; her capacity I mean to take the floor in any company, to represent her country, to visit Chatsworth, to control silver, servants, chow dogs, her motherhood…her in short being (what I have never been) a real woman”.

Woolf was inspired by Sackville-West to write one of her most famous novels, Orlando, featuring a protagonist who changes sex over the centuries. This work was described by Sackville-West’s son Nigel Nicolson as “the longest and most charming love-letter in literature.” Unusually, Woolf documented the moment of the conception of Orlando: she wrote in her diary on 5 October 1927: “And instantly the usual exciting devices enter my mind: a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando: Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other” (excerpt from her diary published posthumously by her husband Leonard Woolf).

One of Vita’s male suitors was Henry Lascelles, who would later marry the Princess Royal and become the 6th Earl of Harewood. Vita Sackville-West also had a passionate affair between 1929 and 1931 with Hilda Matheson, head of the BBC Talks Department. She called Hilda by the pet name of “Stoker” during their liaison.

In 1931, Sackville-West was in a ménage à trois with journalist Evelyn Irons, who had interviewed her after her novel The Edwardians was published and became a best-seller, and Irons’s lover, Olive Rinder.

Sackville-West’s long narrative poem, The Land, won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927. She won it again, becoming the only writer to do so, in 1933 with her Collected Poems.

She died at Sissinghurst on 2 June 1962, aged 70. Sissinghurst Castle is now owned by the National Trust, given by Sackville-West’s son Nigel to escape payment of inheritance taxes.

A recording was made of Sackville-West reading from her poem The Land. This was on four 78rpm sides in the Columbia Records ‘International Educational Society’ Lecture series, Lecture 98 (Cat. no. D 40192/3).

Verse

- A man and his loves make a man and his life.

- “A Saxon Song” (1923)

- The dusk is heavy with the wine’s warm load;

Here the long sense of classic measure cures

The spirit weary of its difficult pain;

Here the old Bacchic piety endures,

Here the sweet legends of the world remain.- “Tuscany” in The Best Poems of 1923 (1924) edited by Thomas Moult

- Who could so watch, and not forget the rack

Of wills worn thin and thought become too frail,

Nor roll the centuries back —

And feel the sinews of his soul grow hale,

And know himself for Rome’s inheritor?- “Tuscany” in The Best Poems of 1923 (1924) edited by Thomas Moult

- If I had only loved your flesh

And careless damned your soul to Hell,

I might have laughed and loved afresh,

And loved as lightly and as well,

And little more to tell.- “Song” in The Best Poems of 1923 (1924) edited by Thomas Moult

She walks among the loveliness she made,

Between the apple-blossom and the water—

She walks among the patterned pied brocade,

Each flower her son, and every tree her daughter.

- “The Island”, in Bulletin of the Garden Club of America (1929), p. 1, also in Collected Poems (1934), p. 54

- And so it ends,

We who were lovers may be friends.

I have some weeks in which to steel

My heart and teach myself to feel

Only a sober tenderness

Where once was passion’s loveliness.- “And so it ends”, a poem cited as probably directed to her sister-in-law, Gwen St. Aubyn, in V. Sackville-West : A Critical Biography (1974) by Michael Stevens, p. 91

- You took me weak and unprepared.

I had not thought that you who shared

My days, my nights, my heart, my life,

Would slash me with a naked knife

And gently tell me not to bleed

But to accept your crazy creed.- “And so it ends”, quoted in V. Sackville-West : A Critical Biography (1974) by Michael Stevens, p. 91

- Darling, I thought of nothing mean;

I thought of killing straight and clean.

You’re safe; that’s gone, that wild caprice,

But tell me once before I cease,

Which does your Church esteem the kinder role,

To kill the body or destroy the soul?- “And so it ends” quoted in V. Sackville-West : A Critical Biography (1974) by Michael Stevens, p. 91

- Days I enjoy are days when nothing happens,

When I have no engagements written on my block,

When no one comes to disturb my inward peace,

When no one comes to take me away from myself

And turn me into a patchwork, a jig-saw puzzle,

A broken mirror that once gave a whole reflection,

Being so contrived that it takes too long a time

To get myself back to myself when they have gone.- “Days I enjoy”, quoted in Vita and Virginia: The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf (1993) by Suzanne Raitt, p. 89

- And what have I to give my friends in the last resort?

An awkwardness, a shyness, and a scrap,

No thing that’s truly me, a bootless waste,

A waste of myself and them, for my life is mine

And theirs presumably theirs, and cannot touch.- “Days I enjoy” quoted in Vita and Virginia: The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf (1993) by Suzanne Raitt, p. 89

Orchard and Vineyard (1921)

- Yes, they were kind exceedingly; most mild

Even in indignation, taking by the hand

One that obeyed them mutely, as a child

Submissive to a law he does not understand.- “Bitterness”

- Remembrance clamoured in him: ‘She was wild and free,

Magnificent in giving; she was blind

To gain or loss, and, loving, loved but me, — but me!- “Bitterness”

- All her youth is gone, her beautiful youth outworn,

Daughter of tarn and tor, the moors that were once her home

No longer know her step on the upland tracks forlorn

Where she was wont to roam.- “Mariana In The North”; also in Country Life Vol. 50 (1921), p. 738

- All her lovers have passed, her beautiful lovers have passed,

The young and eager men that fought for her arrogant hand,

And the only voice which endures to mourn for her at the last

Is the voice of the lonely land.- “Mariana In The North”

Letters

- It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this — But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defences. And I don’t really resent it.

- Letter to Virginia Woolf (21 January 1926), quoted in Love Letters : A Romantic Treasury (1996) by Rick Smith, p. 78

- It is quite true that you have had infinitely more influence on me intellectually than anyone, and for this alone I love you.

- Letter to Virginia Woolf (29 January 1927). as quoted in Granite and Rainbow : The Hidden Life of Virginia Woolf (2000) by Mitchell Leaska, p. 259

It was a real event in my life and my heart to be with you the other day. We do matter to each other, don’t we? however much our ways may have diverged. I think we have got something indestructible between us, haven’t we? … It has been a very strange relationship, ours; unhappy at times, happy at others; but unique in its way, and infinitely precious to me and (may I say?) to you.

What I like about it is that we always come together again however long the gaps in our meetings may have been. Time seems to make no difference.

- Letter to Violet Trefusis (3 September 1950), published in The Other Woman : A Life of Violet Trefusis, including previously unpublished correspondence with Vita Sackville-West (1985) edited by Philippe Jullian and John Nova Phillips, p. 235

Prose

It is necessary to write, if the days are not to slip emptily by. How else, indeed, to clap the net over the butterfly of the moment? for the moment passes, it is forgotten; the mood is gone; life itself is gone. That is where the writer scores over his fellows: he catches the changes of his mind on the hop. Growth is exciting; growth is dynamic and alarming. Growth of the soul, growth of the mind; how the observation of last year seems childish, superficial; how this year — even this week — even with this new phrase — it seems to us that we have grown to a new maturity. It may be a fallacious persuasion, but at least it is stimulating, and so long as it persists, one does not stagnate.

I look back as through a telescope, and see, in the little bright circle of the glass, moving flocks and ruined cities.

- Twelve Days (1928) p.

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 9 March – tried – premiere of Verdi’s Nabucco – art by Tom Roberts – birth of Vita Sackville-West"