Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse. Follow us on twitter @cowboycoleridge. Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

© copyright 2021 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

a need…

for clarity

on the altar,

contentment

the search, the most

important purpose,

or rather

the only one

nothin’ other than

this promise

everything found

in solitude

what is real

must always be

a callin’

chosen

either here

or in the next one

no middle way

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

a need…

to experience

all that beauty

and sorrow

have to offer

to push

mentally

physically

emotionally

for a reminder

to know

if you will come

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

a need…

in the cold, dark hours

when there ain’t no kiddin’

about what has been done

and what has not

for a losin’

all control, fallin’

and lettin’ go,

knowin’ you will

be caught feelin’

too much to ask, after the fall,

to find someone to be the all

© copyright 2017 mac tag/cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

| Marie-Henri Beyle | |

|---|---|

Stendhal, by Olof Johan Södermark, 1840

|

|

Today is the birthday of Stendahl (Marie-Henri Beyle 23 January 1783 Grenoble, France – 23 March 1842 Paris). Perhaps best known for the novels Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839), he is highly regarded for the acute analysis of his characters’ psychology and considered one of the earliest and foremost practitioners of realism.

He formed a particular attachment to Italy, where he spent much of the remainder of his career, serving as French consul at Trieste and Civitavecchia. His novel The Charterhouse of Parma, written in 52 days, is set in Italy, which he considered a more sincere and passionate country than Restoration France. An aside in that novel, referring to a character who contemplates suicide after being jilted, speaks about his attitude towards his home country: “To make this course of action clear to my French readers, I must explain that in Italy, a country very far away from us, people are still driven to despair by love.”

Stendhal was a an inveterate womaniser. His genuine empathy towards women is evident in his books. Simone de Beauvoir spoke highly of him in The Second Sex. One of his early works is On Love, a rational analysis of romantic passion that was based on his unrequited love for Mathilde, Countess Dembowska, whom he met while living at Milan. In his writing he was able to fuse the tension between clear-headed analysis and romantic feeling. He could be considered a Romantic realist.

Stendhal suffered miserable physical disabilities in his final years as he continued to produce some of his most famous work. As he noted in his journal, he was taking iodide of potassium and quicksilver to treat his syphilis. Stendhal died a few hours after collapsing with a seizure on the streets of Paris. He is interred in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Prose

- Presque tous les malheurs de la vie viennent des fausses idées que nous avons sur ce qui nous arrive. Connaître à fond les hommes, juger sainement des événements, est donc un grand pas vers le bonheur.

- Almost all our misfortunes in life come from the wrong notions we have about the things that happen to us. To know men thoroughly, to judge events sanely, is, therefore, a great step towards happiness.

- Journal entry (10 December 1801)

- Almost all our misfortunes in life come from the wrong notions we have about the things that happen to us. To know men thoroughly, to judge events sanely, is, therefore, a great step towards happiness.

- Comme homme, j’ai le cœur 3 ou 4 fois moins sensible, parce que j’ai 3 ou 4 fois plus de raison et d’expérience du monde, ce que vous autres femmes appelez dureté de cœur.Comme homme, j’ai la ressource d’avoir des maîtresses. Plus j’en ai et plus le scandale est grand, plus j’acquiers de réputation et de brillant dans le monde.

- Since I am a man, my heart is three or four times less sensitive, because I have three or four times as much power of reason and experience of the world — a thing which you women call hard-heartedness.

As a man, I can take refuge in having mistresses. The more of them I have, and the greater the scandal, the more I acquire reputation and brilliance in society. - Letter to his sister Pauline (29 August 1804)

- Since I am a man, my heart is three or four times less sensitive, because I have three or four times as much power of reason and experience of the world — a thing which you women call hard-heartedness.

- Je ne vois qu’une règle: être clair. Si je ne suis pas clair, tout mon monde est anéanti.

- I see but one rule: to be clear. If I am not clear, all my world crumbles to nothing.

- Letter to Honoré de Balzac, Civita Vecchia (30 October 1840)

- I see but one rule: to be clear. If I am not clear, all my world crumbles to nothing.

- L’amour a toujours été pour moi la plus grande des affaires ou plutôt la seule.

- Love has always been the most important business in my life; I should say the only one.

- La Vie d’Henri Brulard (1890)

- Variant translation: Love has always been the most important business in my life, or rather the only one.

- Love has always been the most important business in my life; I should say the only one.

De L’Amour (On Love) (1822)

- La beauté n’est que la promesse du bonheur.

- Beauty is nothing other than the promise of happiness.

- Ch. 17, footnote

- Beauty is nothing other than the promise of happiness.

- On peut tout acquérir dans la solitude, hormis du caractère.

- One can acquire everything in solitude — except character.

- Fragments

- One can acquire everything in solitude — except character.

Armance (1827)

- Pourquoi ne pas en finir? se dit-il enfin; pourquoi cette obstination à lutter contre le destin qui m’accable? J’ai beau faire les plans de conduite les plus raisonnables en apparence, ma vie n’est qu’une suite de malheurs et de sensations amères. Ce mois-ci ne vaut pas mieux que le mois passé; cette année-ci ne vaut pas mieux que l’autre année; d’où vient cette obstination à vivre? Manquerais-je de fermeté? Qu’est-ce que la mort? se dit-il en ouvrant la caisse de ses pistolets et les considérant. Bien peu de chose en vérité; il faut être fou pour s’en passer.

- “Why not make an end of it all?” he asked himself. “Why this obstinate resistance to the fate that is crushing me? It is all very well my forming what are apparently the most reasonable forms of conduct, my life is a succession of griefs and bitter feelings. This month is no better than the last; this year is no better than last year. Why this obstinate determination to go on living? Can I be wanting in firmness? What is death?” he asked himself, opening his case of pistols and examining them. “A very small matter, when all is said; only a fool would be concerned about it.”

- Ch. 2

- “Why not make an end of it all?” he asked himself. “Why this obstinate resistance to the fate that is crushing me? It is all very well my forming what are apparently the most reasonable forms of conduct, my life is a succession of griefs and bitter feelings. This month is no better than the last; this year is no better than last year. Why this obstinate determination to go on living? Can I be wanting in firmness? What is death?” he asked himself, opening his case of pistols and examining them. “A very small matter, when all is said; only a fool would be concerned about it.”

- Cette manie des mères de ce siècle, d’être constamment à la chasse au mari.

- This mania of the mothers of the period, to be constantly in pursuit of a son-in-law.

- Ch. 5

- This mania of the mothers of the period, to be constantly in pursuit of a son-in-law.

- Ce qui est fort beau est nécessairement toujours vrai.

- What is really beautiful must always be true.

- Ch. 6

- What is really beautiful must always be true.

Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black) (1830)

- Dans notre état, il faut opter; il s’agit de faire fortune dans ce monde ou dans l’autre, il n’y a pas de milieu.

- In our calling, we have to choose; we must make our fortune either in this world or in the next, there is no middle way.

- Vol. I, ch. VIII

- In our calling, we have to choose; we must make our fortune either in this world or in the next, there is no middle way.

- Quitte-t-on sa maîtresse, on risque, hélas! d’être trompé deux ou trois fois par jour.

- When a man leaves his mistress, he runs the risk of being betrayed two or three times daily.

- Vol. I, ch. XII

- Jamais il ne s’était trouvé aussi près de ces terribles instruments de l’artillerie féminine.

- Never had he found himself so close to those terrible weapons of feminine artillery.

- Vol. I, ch. XVI

- Never had he found himself so close to those terrible weapons of feminine artillery.

- Les vraies passions sont égoïstes.

- Our true passions are selfish.

- Vol. I, ch. XXI

- Our true passions are selfish.

- C’est à coups de mépris public qu’un mari tue sa femme au XIXe siècle; c’est en lui fermant tous les salons.

- It is with blows dealt by public contempt that a husband kills his wife in the nineteenth century; it is by shutting the doors of all the drawing-rooms in her face.

- Vol. I, ch. XXI

- It is with blows dealt by public contempt that a husband kills his wife in the nineteenth century; it is by shutting the doors of all the drawing-rooms in her face.

- Que ne sait-il choisir ses gens? La marche ordinaire du XIXe siècle est que, quand un être puissant et noble rencontre un homme de cœur, il le tue, l’exile, l’emprisonne ou l’humilie tellement, que l’autre a la sottise d’en mourir de douleur.

- Why does he not know how to select servants? The ordinary procedure of the nineteenth century is that when a powerful and noble personage encounters a man of feeling, he kills, exiles, imprisons or so humiliates him that the other, like a fool, dies of grief.

- Vol. I, ch. XXIII

- Why does he not know how to select servants? The ordinary procedure of the nineteenth century is that when a powerful and noble personage encounters a man of feeling, he kills, exiles, imprisons or so humiliates him that the other, like a fool, dies of grief.

- Étrange effet du mariage, tel que l’a fait le XIXe siècle! L’ennui de la vie matrimoniale fait périr l’amour sûrement, quand l’amour a précédé le mariage. Et cependant, dirait un philosophe, il amène bientôt chez les gens assez riches pour ne pas travailler, l’ennui profond de toutes les jouissances tranquilles. Et ce n’est que les âmes sèches parmi les femmes qu’il ne prédispose pas à l’amour.

- A strange effect of marriage, such as the nineteenth century has made it! The boredom of married life inevitably destroys love, when love has preceded marriage. And yet, as a philosopher has observed, it speedily brings about, among people who are rich enough not to have to work, an intense boredom with all quiet forms of enjoyment. And it is only dried up hearts, among women, that it does not predispose to love.

- Vol. I, ch. XXIII

- Les contemporains qui souffrent de certaines choses ne peuvent s’en souvenir qu’avec une horreur qui paralyse tout autre plaisir, même celui de lire un conte.

- People who have been made to suffer by certain things cannot be reminded of them without a horror which paralyses every other pleasure, even that to be found in reading a story.

- Vol. I, ch. XXVII

- People who have been made to suffer by certain things cannot be reminded of them without a horror which paralyses every other pleasure, even that to be found in reading a story.

- J.-J. Rousseau, répondit-il, n’est à mes yeux qu’un sot, lorsqu’il s’avise de juger le grand monde; il ne le comprenait pas, et y portait le cœur d’un laquais parvenu… Tout en prêchant la république et le renversement des dignités monarchiques, ce parvenu est ivre de bonheur, si un duc change la direction de sa promenade après dîner, pour accompagner un de ses amis.

- “Jean Jacques Rousseau,” he answered, “is nothing but a fool in my eyes when he takes it upon himself to criticise society; he did not understand it, and approached it with the heart of an upstart flunkey…. For all his preaching a Republic and the overthrow of monarchical titles, the upstart is mad with joy if a Duke alters the course of his after-dinner stroll to accompany one of his friends.”

- Vol. II, ch. VIII

- “Jean Jacques Rousseau,” he answered, “is nothing but a fool in my eyes when he takes it upon himself to criticise society; he did not understand it, and approached it with the heart of an upstart flunkey…. For all his preaching a Republic and the overthrow of monarchical titles, the upstart is mad with joy if a Duke alters the course of his after-dinner stroll to accompany one of his friends.”

- Tel est le malheur de notre siècle, les plus étranges égarements même ne guérissent pas de l’ennui.

- This is the curse of our age, even the strangest aberrations are no cure for boredom.

- Vol. II, ch. XVII

- This is the curse of our age, even the strangest aberrations are no cure for boredom.

- Un roman est un miroir qui se promène sur une grande route. Tantôt il reflète à vos yeux l’azur des cieux, tantôt la fange des bourbiers de la route. Et l’homme qui porte le miroir dans sa hotte sera par vous accusé‚ d’être immoral ! Son miroir montre la fange, et vous accusez le miroir! Accusez bien plutôt le grand chemin où est le bourbier, et plus encore l’inspecteur des routes qui laisse l’eau croupir et le bourbier se former.

- A novel is a mirror carried along a high road. At one moment it reflects to your vision the azure skies at another the mire of the puddles at your feet. And the man who carries this mirror in his pack will be accused by you of being immoral! His mirror shews the mire, and you blame the mirror! Rather blame that high road upon which the puddle lies, still more the inspector of roads who allows the water to gather and the puddle to form.

- Vol. II, ch. XIX

- A novel is a mirror carried along a high road. At one moment it reflects to your vision the azure skies at another the mire of the puddles at your feet. And the man who carries this mirror in his pack will be accused by you of being immoral! His mirror shews the mire, and you blame the mirror! Rather blame that high road upon which the puddle lies, still more the inspector of roads who allows the water to gather and the puddle to form.

La Chartreuse de Parme (The Charterhouse of Parma) (1839)

-

- Because one has little fear of shocking vanity in Italy, people adopt an intimate tone very quickly and discuss personal things.

- Ch. 6

- Because one has little fear of shocking vanity in Italy, people adopt an intimate tone very quickly and discuss personal things.

- A la Scala, il est d’usage de ne faire durer qu’une vingtaine de minutes ces petites visites que l’on fait dans les loges.

- At La Scala it is customary to take no more than twenty minutes for those little visits one pays to boxes.

- Ch. 6

- At La Scala it is customary to take no more than twenty minutes for those little visits one pays to boxes.

- Les plaisirs et les soins de l’ambition la plus heureuse, même du pouvoir sans bornes, ne sont rien auprès du bonheur intime que donnent les relations de tendresse et d’amour. Je suis homme avant d’être prince, et, quand j’ai le bonheur d’aimer, ma maîtresse s’adresse à l’homme et non au prince.

- The pleasures and the cares of the luckiest ambition, even of limitless power, are nothing next to the intimate happiness that tenderness and love give. I am a man before being a prince, and when I have the good fortune to be in love my mistress addresses a man and not a prince.

- Ch. 7

- The pleasures and the cares of the luckiest ambition, even of limitless power, are nothing next to the intimate happiness that tenderness and love give. I am a man before being a prince, and when I have the good fortune to be in love my mistress addresses a man and not a prince.

- Quand je devrais acheter cette vie de délices et cette chance unique de bonheur par quelques petits dangers, où serait le mal? Et ne serait-ce pas encore un bonheur que de trouver ainsi une faible occasion de lui donner une preuve de mon amour?

- Were I to buy this life of pleasure and this only chance at happiness with a few little dangers, where would be the harm? And wouldn’t it still be fortunate to find a weak excuse to give her proof of my love?

- Ch. 20

- Were I to buy this life of pleasure and this only chance at happiness with a few little dangers, where would be the harm? And wouldn’t it still be fortunate to find a weak excuse to give her proof of my love?

- Une femme de quarante ans n’est plus quelque chose que pour les hommes qui l’ont aimée dans sa jeunesse!

- A forty-year-old woman is only something to men who have loved her in her youth!

- Ch. 23

- A forty-year-old woman is only something to men who have loved her in her youth!

| Édouard Manet | |

|---|---|

portrait by Nadar, 1874

|

|

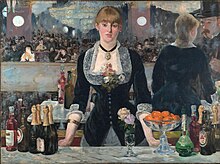

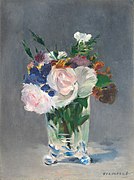

Today is the birthday of Édouard Manet (Paris; 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883 Paris); painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, and a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born into an upper-class household with strong political connections, Manet rejected the future originally envisioned for him, and became engrossed in the world of painting. His early masterworks, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe) and Olympia, both 1863, caused great controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the genesis of modern art. The last 20 years of Manet’s life saw him form bonds with other great artists of the time, and develop his own style that would be heralded as innovative and serve as a major influence for future painters.

Manet married Suzanne Leenhoff in 1863. Leenhoff was a Dutch-born piano teacher of Manet’s age with whom he had been romantically involved for approximately ten years. Leenhoff initially had been employed by Manet’s father, Auguste, to teach Manet and his younger brother piano. She also may have been Auguste’s mistress. Manet painted his wife in The Reading, among other paintings.

In April 1883, his left foot was amputated because of gangrene, and he died eleven days later in Paris. He is buried in the Passy Cemetery in the city.

Gallery

Femme devant un miroir. 1877

-

The Absinthe Drinker c. 1859, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

-

The Spanish Singer, 1860 Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The surprised nymph, 1861, National Museum of Fine Arts, Buenos Aires

-

The Old Musician, 1862, National Gallery of Art

-

Mlle. Victorine in the Costume of a Matador, 1862, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama, 1864, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Inspired by the Battle of Cherbourg (1864)

-

Dead Matador, 1864–65, National Gallery of Art

-

The Philosopher, (Beggar with Oysters), 1864–67, Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Ragpicker, 1865–70, Norton Simon Museum

-

The Reading, 1865–1873

-

Young Flautist, or The Fifer, 1866, Musée d’Orsay

-

Still Life with Melon and Peaches, 1866, National Gallery of Art

-

The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866, National Gallery of Art

-

Woman with Parrot, 1866, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Guitar Player, c.1866, Hill-Stead Museum

-

Portrait of Madame Brunet, 1867, J. Paul Getty Museum

-

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1868

-

Portrait of Émile Zola, 1868, Musée d’Orsay

-

Breakfast in the Studio (the Black Jacket), 1868, New Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

-

The Balcony, 1868–69, Musée d’Orsay

-

Gypsy with a Cigarette, ca.1860s–1870s, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Boating, 1874, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Portrait of Abbé Hurel, 1874, National Museum of Decorative Arts, Buenos Aires

-

The grand canal of Venice (Blue Venice), 1875, Shelburne Museum

-

Madame Manet, 1874–76, Norton Simon Museum

-

Portrait of Stéphane Mallarmé, 1876, Musée d’Orsay

-

Nana, 1877, Hamburger Kunsthalle

-

The Rue Mosnier with Flags, 1878, J. Paul Getty Museum

-

The Plum, 1878, National Gallery of Art

-

In the Conservatory, 1879, National Gallery, Berlin

-

Chez le père Lathuille, 1879, Musée des Beaux-Arts Tournai

-

The Bugler, 1882, Dallas Museum of Art

-

House in Rueil, 1882, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

-

Garden Path in Rueil, 1882, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon

-

Flowers in a Crystal Vase, 1882, National Gallery of Art

-

Still Life, Lilac Bouquet, 1883

| Marchesa Luisa Casati |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Marchesa Luisa Casati by Adolf de Meyer

|

|

Today is the birthday of Luisa, Marchesa Casati Stampa di Soncino (Milan 23 January 1881 – 1 June 1957 Knightsbridge, London), also known as Luisa Casati; heiress, muse, and patroness of the arts in early 20th-century Europe known for her eccentricities. As the concept of quaintrelle was re-developed, Marchesa Casati fitted the utmost example by saying: “I want to be a living work of art”.

In 1900, she married Camillo, Marchese Casati Stampa di Soncino (Muggiò, 12 August 1877 – Roma, 18 September 1946). The Casatis maintained separate residences for the duration of their marriage. They were legally separated in 1914. They remained married until Marchese Casati’s death in 1946.

A celebrity and femme fatale, the Marchesa’s famous eccentricities dominated and delighted European society for nearly three decades. The beautiful and extravagant hostess to the Ballets Russes was something of a legend among her contemporaries. She astonished society by parading with a pair of leashed cheetahs and wearing live snakes as jewellery.

She captivated artists and literary figures such as Robert de Montesquiou, Romain de Tirtoff (Erté), Jean Cocteau, and Cecil Beaton. She had a long term affair with the author Gabriele d’Annunzio, who is said to have based on her the character of Isabella Inghirami in Forse che si forse che no (Maybe yes, maybe no) (1910). The character of La Casinelle, who appeared in two novels by Michel Georges-Michel, Dans la fete de Venise (1922) and Nouvelle Riviera (1924), was also inspired by her.

In 1910, Casati took up residence at the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, on Grand Canal in Venice (now the home of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection). Her soirées there would become legendary. Casati collected a menagerie of exotic animals, and patronized fashion designers such as Fortuny and Poiret. From 1919 to 1920 she lived at Villa San Michele in Capri, the tenant of the unwilling Axel Munthe. Her time on the Italian island, tolerant home to a wide collection of artists, gay men, and lesbians in exile, was described by British author Compton Mackenzie in his diaries.

Her numerous portraits were painted and sculpted by artists as various as Giovanni Boldini, Paolo Troubetzkoy, Romaine Brooks (with whom she had an affair), Kees van Dongen, and Man Ray; many of them she paid for, as a wish to “commission her own immortality”. She was muse to Italian Futurists such as F. T. Marinetti, Fortunato Depero, and Umberto Boccioni. Augustus John’s portrait of her is one of the most popular paintings at the Art Gallery of Ontario; Jack Kerouac wrote poems about it and Robert Fulford was impressed by it as a schoolboy.

By 1930, Casati had amassed a personal debt of $25 million. Unable to pay her creditors, her personal possessions were auctioned off. Designer Coco Chanel was reportedly one of the bidders.

Casati fled to London where she lived in comparative poverty in a one-room flat. She was rumoured to be seen rummaging in bins searching for feathers to decorate her hair. On 1 June 1957, Marchesa Casati died of a stroke at her last residence at 32 Beaufort Gardens in Knightsbridge, aged 76. Following a requiem mass at Brompton Oratory, the Marchesa was interred in Brompton Cemetery.

She was buried wearing her black and leopard skin finery and a pair of false eyelashes. She was also interred with one of her beloved stuffed pekinese dogs. Her tombstone is a small grave marker in the shape of an urn draped in cloth with a swag of flowers to the front. The inscription on the tombstone, which misspells her “Louisa” rather than “Luisa”, is inscribed with the quote, “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety”, from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra.

Gallery

Reclinabile Nudo by Giovanni Boldini

By Augustus John

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 23 January – a need – prose by Stendahl – art by Édouard Manet – birth of Luisa Casati"