Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse. Follow us on twitter @cowboycoleridge. Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

© copyright 2021 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

redemption

big word carryin’

a heavy load

would not be

too far wrong

to suggest

some serious time

should be spent

on my knees

seekin’ nothin’ else

so, we get this

all i have left

not searchin’

for higher ground

just tryin’ to find

the ground

where i belong

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

the struggle within

continues between

the man who has given up

and the man who still believes

di tale amor

words can hardly describe

stride la vampa

the flames were roarin’

and when they were

the choices made

did not work out

so well, but now,

a certain sort

of welcomed

clarity has come

vedi le fosche notturne

see, the night sky

deserto sulla terra

alone with this vision

if that is meant to be

then so shall it be

but, supposin’,

for the sake of my friends

if nothin’ else, that hope

does exist, then

la luce di un sorriso

the light of a smile,

how could i resist

ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere

ah yes, in bein’ yours

ai nostri monti ritorneremo

to our mountains we shall return

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

This is how you help me. I have always wanted to write somethin’ called “Without You”. There are so many good songs with that title. I even like Van Halen’s song and Motley Crue‘s (I leave absolutely no stone not turned in my continuin’ and never endin’ search for inspiration and beauty). This started comin’ the other day when I was drivin’, as they so often do. I have escaped the past few days by allowin’ myself the luxury of imaginin’ bein’ with the one and this is what I saw:

Without You

I can be everything

I can be anything

I can do not a thing

I can be very strong

I can go on too long

I can even be wrong

I can be sometimes right

I can reach for the light

I can follow the night

I can be counted on

I can be relied on

I can be banked on

I can make a firm stand

I can lend a strong hand

I can live off the land

I can be all alone

I can go on my own

I can dare the unknown

I can be all of that and this

I can stare into the abyss

I can do these things and much more

I can cherish, love and adore

But there is one thing I can’t do

I just cannot be without you

Without you, cannot imagine

Without you life is just livin’

Without you I would be so lost

Without you, cannot bear the cost

Without you, days controlled by doubt

Without you, just bein’ without

© copyright 2012 mac tag/Cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

Today is the birthday of philosopher Auguste Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857). His muse was Clotilde de Vaux. They met in October 1844 and Comte fell in love with her. Clotilde was married but her husband had abandoned her. Yet bein’ a devote Catholic, she firmly rejected Comte. She agreed to follow up with their correspondence and Comte’s passionate love kept growin’ until Clotilde suddenly died of tuberculosis a year later. Comte was highly impressed by her moral superiority and he was inspired to form the secular religion, Religion of Humanity.

Today is the birthday of philosopher Auguste Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857). His muse was Clotilde de Vaux. They met in October 1844 and Comte fell in love with her. Clotilde was married but her husband had abandoned her. Yet bein’ a devote Catholic, she firmly rejected Comte. She agreed to follow up with their correspondence and Comte’s passionate love kept growin’ until Clotilde suddenly died of tuberculosis a year later. Comte was highly impressed by her moral superiority and he was inspired to form the secular religion, Religion of Humanity.

| Edgar Allan Poe | |

|---|---|

1849 “Annie” daguerreotype of Poe

|

|

Today is the birthday of Edgar Allan Poe (Boston; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849 Baltimore); writer, editor, and literary critic. Perhaps best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism in the United States and American literature as a whole, and he was one of the country’s earliest practitioners of the short story. Poe is generally considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre and is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

In January 1845, Poe published his poem “The Raven” to instant success. His wife died of tuberculosis two years after its publication. Poe died at age 40; the cause of his death is unknown and has been variously attributed to alcohol, brain congestion, cholera, drugs, heart disease, rabies, suicide, tuberculosis, and other agents.

Poe and his works influenced literature in the United States and around the world. Poe and his work appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. The Mystery Writers of America present an annual award known as the Edgar Award for distinguished work in the mystery genre.

One evening in January 1842, Virginia showed the first signs of consumption, now known as tuberculosis, while singing and playing the piano. Poe described it as breaking a blood vessel in her throat. She only partially recovered. Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of Virginia’s illness. Biographers and critics often suggest that Poe’s frequent theme of the “death of a beautiful woman” stems from the repeated loss of women throughout his life, including his wife.

Poe was increasingly unstable after his wife’s death. He attempted to court poet Sarah Helen Whitman who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe’s drinking and erratic behavior. Poe then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with his childhood sweetheart Sarah Elmira Royster.

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore, “in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance”, according to Joseph W. Walker who found him. He was taken to the Washington Medical College where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849 at 5:00 in the morning. Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own. He is said to have repeatedly called out the name “Reynolds” on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring. Some sources say that Poe’s final words were “Lord help my poor soul”. All medical records have been lost, including his death certificate.

Quotes

- A dark unfathom’d tide

Of interminable pride —

A mystery, and a dream,

Should my early life seem.- “Imitation”, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827).

- O, human love! thou spirit given,

On Earth, of all we hope in Heaven!- “Tamerlane”, l. 177 (1827).

- The happiest day — the happiest hour

My sear’d and blighted heart hath known,

The highest hope of pride and power,

I feel hath flown.- “The Happiest Day”, st. 1 (1827).

- Sound loves to revel in a summer night.

- Al Aaraaf (1829).

- Years of love have been forgot

In the hatred of a minute.- To M——— (1829), reported in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, 10th ed. (1919).

- From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were — I have not seen

As others saw — I could not bring

My passions from a common spring —

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow — I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone —

And all I lov’d — I lov’d alone —- “Alone”, l. 1-8 (written 1829, published 1875).

- And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view.- “Alone”, l. 20-22.

- Hast thou not torn the Naiad from her flood,

The Elfin from the green grass, and from me

The summer dream beneath the tamarind tree?- “Sonnet. To Science”, l. 12-14 (1829). — “.

- Helen, thy beauty is to me

Like those Nicean barks of yore,

That gently, o’er a perfumed sea,

The weary, wayworn wanderer bore

To his own native shore. - On desperate seas long wont to roam,

Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face,

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home

To the glory that was Greece

And the grandeur that was Rome.- “To Helen”, st. 1-2 (1831).

- Yes, Heaven is thine; but this

Is a world of sweets and sours;

Our flowers are merely—flowers.- “Israfel”, st. 7 (1831).

- If I could dwell

Where Israfel

Hath dwelt, and he where I,

He might not sing so wildly well

A mortal melody,

While a bolder note than this might swell

From my lyre within the sky.- “Israfel”, st. 8 (1831).

- Come! let the burial rite be read — the funeral song be sung! —

An anthem for the queenliest dead that ever died so young —

A dirge for her the doubly dead in that she died so young.- “Lenore”, st. 1 (1831).

- Vastness! and Age! and Memories of Eld!

Silence! and Desolation! and dim Night!

I feel ye now — I feel ye in your strength.- “The Coliseum”, st. 2 (1833).

- Thou wast that all to me, love,

For which my soul did pine —

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine.- “To One in Paradise”, st. 1 (1834).

- And all my days are trances,

And all my nightly dreams

Are where thy grey eye glances,

And where thy footstep gleams —

In what ethereal dances,

By what eternal streams.- “To One In Paradise”, st. 4; variants of this verse read “where thy dark eye glances”. ).

- In the greenest of our valleys

By good angels tenanted,

Once a fair and stately palace —

Radiant palace — reared its head.- “The Haunted Palace” (1839), st. 1.

- This—all this—was in the olden

Time long ago.- “The Haunted Palace” (1839), st. 2.

- While, like a ghastly rapid river,

Through the pale door

A hideous throng rush out forever

And laugh — but smile no more.- “The Haunted Palace” (1839), st. 5.).

- They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.

- “Eleonora” (1841).

- While the angels, all pallid and wan,

Uprising, unveiling, affirm

That the play is the tragedy, “Man”,

And its hero the Conqueror Worm.- “The Conqueror Worm” (1843), st. 5.

- .By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule —

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE — out of TIME.- “Dreamland”, st. 1 (1845).

- Thou wouldst be loved? — then let thy heart

From its present pathway part not!

Being everything which now thou art,

Be nothing which thou art not.

So with the world thy gentle ways,

Thy grace, thy more than beauty,

Shall be an endless theme of praise,

And love — a simple duty.- “To Frances S. Osgood” (1845).

- Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado.- “Eldorado”, st. 1 (1849).

- “Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

Ride, boldly ride,”

The shade replied, —

“If you seek for Eldorado!”- “Eldorado”, st. 4.

- You are not wrong, who deem

That my days have been a dream;

Yet if hope has flown away

In a night, or in a day,

In a vision, or in none,

Is it therefore the less gone?

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.- “A Dream Within a Dream” (1849).

- O God! Can I not save

One from the pitiless wave?

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?- “A Dream Within A Dream” (1849).

- Thank Heaven! the crisis —

The danger is past,

And the lingering illness

Is over at last —

And the fever called “Living”

Is conquered at last.- “For Annie”, st. 1 (1849).

- Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells.- “The Bells”, st. 1 (1849).

- Hear the mellow wedding bells

Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight!- “The Bells”, st. 2 (1849).

The City in the Sea (1831)

- Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.- St. 1.

- So blend the turrets and shadows there

That all seem pendulous in air,

While from a proud tower in the town

Death looks gigantically down.- St. 2.

- And when, amid no earthly moans,

Down, down that town shall settle hence,

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones,

Shall do it reverence.- St. 5.

The Raven (1844)

- Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.- Stanza 1.

- Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.- Stanza 2.

- Sorrow for the lost Lenore —

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore —

Nameless here for evermore.- Stanza 2.

- And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me — filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before.- Stanza 3.

- Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.- Stanza 5.

- Perched upon a bust of Pallas, just above my chamber door,—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.- Stanza 7.

- “Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore —

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”- Stanza 8.

- “Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore.- Stanza 11

- “Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! — prophet still, if bird or devil!”

- Stanza 15.

- “Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! — quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”- Stanza 17.

- And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door.- Stanza 18.

- And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted — nevermore!- Stanza 18.

Ulalume (1847)

- The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crisped and sere —

The leaves they were withering and sere;

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year.- St. 1.

- Here once, through an alley Titanic,

Of cypress, I roamed with my Soul —

Of cypress, with Psyche, my Soul.- St. 2.

- Thus I pacified Psyche and kissed her,

And tempted her out of her gloom.- St. 8.

Annabel Lee (1849)

- It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee; —

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.- St. 1.

- I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea,

But we loved with a love that was more than love —

I and my Annabel Lee —

With a love that the wingèd seraphs of Heaven

Coveted her and me.- St. 2.

- But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we —

Of many far wiser than we —

And neither the angels in Heaven above

Nor the demons down under the sea

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee- St. 5.

- In her sepulcher there by the sea —

In her tomb by the sounding sea.- St. 6.

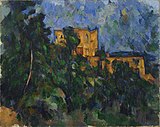

| Paul Cézanne | |

|---|---|

Paul Cézanne, c. 1861

|

|

And today is the birthday of Paul Cézanne (Aix-en-Provence; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906 Aix-en-Provence); artist and Post-Impressionist painter. Cézanne’s often repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of colour and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields. The paintings convey Cézanne’s intense study of his subjects.

Cézanne formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century’s new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism. Both Matisse and Picasso reportedly said that Cézanne “is the father of us all.”

One day, Cézanne was caught in a storm while working in the field. Only after working for two hours under a downpour did he decide to go home; but on the way he collapsed. He was taken home by a passing driver. His old housekeeper rubbed his arms and legs to restore the circulation; as a result, he regained consciousness. On the following day, he intended to continue working, but later on he fainted; the model with whom he was working called for help; he was put to bed, and he never left it. He died a few days later, on 22 October 1906 of pneumonia and was buried at the Saint-Pierre Cemetery in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence.

Gallery

Les Baigneuses

-

A Modern Olympia

1873–1874

Musee d’Orsay, Paris

The Riaux Valley near L’Estaque

1883 -

The Bay of Marseilles, view from L’Estaque

1885 -

Jas de Bouffan 1885–1887 Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Bather

1885–1887

Museum of Modern Art -

The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

1885-1887

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection -

Mardi Gras (Pierrot et Arlequin)

1888

Pushkin Museum, Moscow -

Boy in a Red Waistcoat

1888–1890

National Gallery of Art -

Madame Cézanne in the Greenhouse

1890–1892

Musée de l’Orangerie -

The House with the Cracked Walls

1892–1894

Metropolitan Museum of Art -

Maison Maria on the way to the Château Noir

1895

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas -

Château Noir

1900–1904

National Gallery of Art, Washington, US -

Mont Sainte-Victoire and Château Noir

1904 – 1905

Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan -

The Bathers

1898–1905

National Gallery, London, UK

-

Still Life with an Open Drawer

1867 – 1869

Musée d’Orsay

-

Self-portrait

1895 -

Three Pears, ca. 1888-90, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Pine Tree in Front of the Caves above Château Noir, ca. 1900, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Study of a Skull, 1902–04, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit, 1906, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

-

Portrait of Achille Emperaire

1868

Musée d’Orsay -

Paul Alexis reading to Émile Zola

1869–1870

São Paulo Museum of Art -

Madame Cézanne

1885–87

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum -

Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress

c. 1890-1894

São Paulo Museum of Art -

Portrait of Gustave Geffroy

1895

Musée d’Orsay

Woman with a Coffeepot

Oil on canvas

c. 1895

Musée d’Orsay.

On this day in 1853 – Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Il trovatore receives its premiere performance in Rome.

Anna Netrebko (detail)

as Leonora at the Salzburg Festival 2014 |

|

Il trovatore (“The Troubadour”) is an opera in four acts by Verdi to an Italian libretto largely written by Salvadore Cammarano, based on the play El trovador (1836) by Antonio García Gutiérrez.

The premiere took place at the Teatro Apollo in Rome, and it soon became popular throughout the operatic world, a success due to Verdi’s work over the previous three years. It began with his January 1850 approach to Cammarano with the idea of Il trovatore. There followed, slowly and with interruptions, the preparation of the libretto, first by Cammarano until his death in mid-1852 and then with the young librettist Leone Emanuele Bardare, which gave the composer the opportunity to propose significant revisions.

Today, in its Italian version, Trovatore is given frequently and is a staple of the standard operatic repertoire.

Synopsis

Act 1: The Duel

Scene 1: The guard room in the castle of Luna (The Palace of Aljafería, Zaragoza, Spain)

Ferrando, the captain of the guards, orders his men to keep watch while Count di Luna wanders restlessly beneath the windows of Leonora, lady-in-waiting to the Princess. Di Luna loves Leonora and is jealous of his successful rival, a troubadour whose identity he does not know. In order to keep the guards awake, Ferrando narrates the history of the count (Aria: Di due figli vivea padre beato / “The good Count di Luna lived happily, the father of two sons”): many years ago, a gypsy was wrongfully accused of having bewitched the youngest of the di Luna children; the child had fallen sick and for this the gypsy had been burnt alive as a witch, her protests of innocence ignored. Dying, she had commanded her daughter Azucena to avenge her, which she did by abducting the baby. Although the burnt bones of a child were found in the ashes of the pyre, the father refused to believe in his son’s death; dying, he commanded his firstborn, the new Count di Luna, to seek Azucena.

Scene 2: Garden in the palace of the princess

Leonora confesses her love for the Troubadour to her confidante, Ines (Tacea la notte placida / “The peaceful night lay silent”… Di tale amor / “A love that words can scarcely describe”), in which she tells how she fell in love with a mystery knight, victor at a tournament: lost track of him when a civil war broke out: then encountered him again, in disguise as a wandering troubadour who sang beneath her window. When they have gone, Count di Luna enters, intending to pay court to Leonora himself, but hears the voice of his rival, in the distance: (Deserto sulla terra / “Alone upon this earth”). Leonora in the darkness briefly mistakes the count for her lover, until the Troubadour himself enters the garden, and she rushes to his arms. The Count challenges his rival to reveal his true identity, which he does: Manrico, a knight now outlawed and under death sentence for his allegiance to a rival prince. Manrico in turn challenges him to call the guards, but the Count regards this encounter as a personal rather than political matter, and challenges Manrico instead to a duel over their common love. Leonora tries to intervene, but cannot stop them from fighting (Trio: Di geloso amor sprezzato / “The fire of jealous love” ).

Act 2: The Gypsy Woman

Scene 1: The gypsies’ camp

The gypsies sing the Anvil Chorus: Vedi le fosche notturne / “See! The endless sky casts off her sombre nightly garb…”. Azucena, the daughter of the Gypsy burnt by the count, is still haunted by her duty to avenge her mother (Aria: Stride la vampa / “The flames are roaring!”). The Gypsies break camp while Azucena confesses to Manrico that after stealing the di Luna baby she had intended to burn the count’s little son along with her mother, but overwhelmed by the screams and the gruesome scene of her mother’s execution, she became confused and threw her own child into the flames instead (Aria: Condotta ell’era in ceppi / “They dragged her in bonds”).

Manrico realises that he is not the son of Azucena, but loves her as if she were indeed his mother, as she has always been faithful and loving to him – and, indeed, saved his life only recently, discovering him left for dead on a battlefield after being caught in ambush. Manrico tells Azucena that he defeated di Luna in their earlier duel, but was held back from killing him by a mysterious power (Duet: Mal reggendo / “He was helpless under my savage attack”): and Azucena reproaches him for having stayed his hand then, especially since it was the Count’s forces that defeated him in the subsequent battle of Pelilla. A messenger arrives and reports that Manrico’s allies have taken Castle Castellor, which Manrico is ordered to hold in the name of his prince: and also that Leonora, who believes Manrico dead, is about to enter a convent and take the veil that night. Although Azucena tries to prevent him from leaving in his weak state (Ferma! Son io che parlo a te! / “I must talk to you”), Manrico rushes away to prevent her from carrying out this intent.

Scene 2: In front of the convent

Di Luna and his attendants intend to abduct Leonora and the Count sings of his love for her (Aria: Il balen del suo sorriso / “The light of her smile” … Per me ora fatale / “Fatal hour of my life”). Leonora and the nuns appear in procession, but Manrico prevents di Luna from carrying out his plans and takes Leonora away with him, although once again leaving the Count behind unharmed, as the soldiers on both sides back down from bloodshed, the Count being held back by his own men.

Act 3: The Son of the Gypsy Woman

Scene 1: Di Luna’s camp Di Luna and his army are attacking the fortress Castellor where Manrico has taken refuge with Leonora (Chorus: Or co’ dadi ma fra poco / “Now we play at dice”). Ferrando drags in Azucena, who has been captured wandering near the camp. When she hears di Luna’s name, Azucena’s reactions arouse suspicion and Ferrando recognizes her as the supposed murderer of the count’s brother. Azucena cries out to her son Manrico to rescue her and the count realizes that he has the means to flush his enemy out of the fortress. He orders his men to build a pyre and burn Azucena before the walls.

Scene 2: A chamber in the castle

Inside the castle, Manrico and Leonora are preparing to be married. She is frightened; the battle with di Luna is imminent and Manrico’s forces are outnumbered. He assures her of his love (Aria, Manrico: Ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere / “Ah, yes, my love, in being yours”), even in the face of death. When news of Azucena’s capture reaches him, he summons his men and desperately prepares to attack (Stretta: Di quella pira l’orrendo foco / “The horrid flames of that pyre”). Leonora faints.

Act 4: The Punishment

Scene 1: Before the dungeon keep

Manrico has failed to free Azucena and has been imprisoned himself. Leonora attempts to free him (Aria: D’amor sull’ali rosee / “On the rosy wings of love”; Chorus & Duet: Miserere / “Lord, thy mercy on this soul”) by begging di Luna for mercy and offers herself in place of her lover. She promises to give herself to the count, but secretly swallows poison from her ring in order to die before di Luna can possess her (Duet: Mira, d’acerbe lagrime / “See the bitter tears I shed”).

Scene 2: In the dungeon

Manrico and Azucena are awaiting their execution. Manrico attempts to soothe Azucena, whose mind wanders to happier days in the mountains (Duet: Ai nostri monti ritorneremo / “Again to our mountains we shall return”). At last the gypsy slumbers. Leonora comes to Manrico and tells him that he is saved, begging him to escape. When he discovers she cannot accompany him, he refuses to leave his prison. He believes Leonora has betrayed him until he realizes that she has taken poison to remain true to him. As she dies in agony in Manrico’s arms she confesses that she prefers to die with him than to marry another (Trio: Prima che d’altri vivere / “Rather than live as another’s”). The count has heard Leonora’s last words and orders Manrico’s execution. Azucena awakes and tries to stop di Luna. Once Manrico is dead, she cries: Egli era tuo fratello! Sei vendicata, o madre. / “He was your brother … You are avenged, oh mother!”

Geraldine Farrar as Manon

And today is the premiere date of Manon; an opéra comique in five acts by Jules Massenet to a French libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille, based on the 1731 novel L’histoire du chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut by the Abbé Prévost. It was first performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris with sets designed by Eugène Carpezat (act 1), Auguste Alfred Rubé and Philippe Chaperon (acts 2 and 3), and Jean-Baptiste Lavastre (act 4).

Prior to Massenet’s work, Halévy (Manon Lescaut, ballet, 1830) and Auber (Manon Lescaut, opéra comique, 1856) had used the subject for musical stage works. Massenet also wrote a one-act sequel to Manon, Le portrait de Manon (1894), involving the Chevalier des Grieux as an older man.

The composer worked at the score of Manon at his country home outside Paris and also at a house at The Hague once occupied by Prévost himself.

Manon is Massenet’s most popular and enduring opera and, having “quickly conquered the world’s stages”, it has maintained an important place in the repertory since its creation. It is the quintessential example of the charm and vitality of the music and culture of the Parisian Belle Époque. In 1893 an opera by Giacomo Puccini entitled Manon Lescaut, and based on the same novel was premiered and has also become popular.

Mac Tag

L’amour pour principe et l’ordre pour base; le progrès pour but (Love as a principle and order as the basis; Progress as the goal). – Auguste Comte

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 19 January – bein’ yours – birth of August Comte – verse by Edgar Allan Poe – premiere of Verdi’s Il trovatore – art by Cézanne – premiere of Massenet’s Manon"