Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse. Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

a moment before ever

words, hear pronounced,

repeat on lips quenched

from needed attention

now this impetus of hope

no more trouble within,

needs be faced

in the bosom of with

as is, and nothin’ else

everything done for beauty,

the dream carries desire,

under your kiss

© copyright 2022 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2021 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

holdin’ you here

suspended

prone spread open

through you, all things

on this that will soon happen

another point of view,

feel you, helpless,

in your arms

these feelin’s without measure

comin’ on, an ardent swarm

such transport is the future

that stirs in you

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

this vision

in the arms of another,

a moment, before forever

words, hear pronounced,

dare repeat on lips parched

from lack thereof

live so little, why this promise

impetus of hope in the heart

a vain challenge to hereafter

or happiness after the fall

an unyieldin’ voice

implacable

no escapin’

trouble within, needs be faced

in the bosom of solitude

as is, or no more

was everything said for beauty,

the dream carries the desire,

under the memory

of her kiss

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge

a loose decision

of the unforgiven

do not deny me

this abode of woe…

watch this vision

in the arms of the Other,

a moment all before forever

“Make the same oath.”

always bold words,

hear pronounced,

that dare repeat

on parched lips

live so little, why this promise

impetus of hope in the heart

a vain challenge to hereafter

for a moment of happiness

a loud unyieldin’ voice

cry to everything “Choose!”

implacable and insensitive

no escapin’

necessary, trouble within,

that which was had and lost

in the bosom of the immense,

like so, and no more

everything was not said, fragile beauty,

invincible dream carries the desire,

under the memory

of her kiss

© copyright 2016 mac tag/cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

| Alfred Stieglitz | |

|---|---|

Stieglitz in 1902 by Gertrude Käsebier

|

|

Today is the birthday of Alfred Stieglitz (Hoboken, New Jersey; January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946 New York City); photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his fifty-year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz was known for the New York art galleries that he ran in the early part of the 20th century, where he introduced many avant-garde European artists to the U.S.

For several years he had known Emmeline Obermeyer, who was the sister of his close friend and business associate Joe Obermeyer. On 16 November 1893, when she turned twenty and Stieglitz was twenty-nine, they married in New York City. Stieglitz later wrote that he did not love Emmy, as she was known, when they were first married and that their marriage was not consummated for at least a year. He indicated that their marriage was one of financial advantage for him (she had inherited money from her father, a wealthy brewery owner) at a time when his own father had lost a great deal of money in the stock market. He quickly regretted his brash decision to marry as he found out that Emmy could not begin to match his own artistic and cultural interests.

In January 1916, Stieglitz was shown a portfolio of drawings by a young artist named Georgia O’Keeffe. Stieglitz was so taken by her art that without meeting O’Keeffe or even getting her permission to show her works he made plans to exhibit her work at 291. The first that O’Keeffe heard about any of this was from another friend who saw her drawings in the gallery in late May of that year. She finally met Stieglitz after going to 291 and chastising him for showing her work without her permission. Stieglitz was immediately attracted to her both physically and artistically. O’Keeffe did not immediately return the interest.

Soon thereafter O’Keeffe met Paul Strand, and her physical and artistic attraction focused on him. She then returned to her home in Texas, and for several months she and Strand exchanged increasingly romantic letters. When Strand told his friend Stieglitz about his new yearning, Stieglitz responded by telling Strand about his own infatuation with O’Keeffe. Gradually Strand’s interest waned, and Stieglitz’s escalated. By the summer of 1917 he and O’Keeffe were writing each other “their most private and complicated thoughts”, and it was clear that something very intense was developing.

The year 1917 marked the end of an era in Stieglitz’s life and the beginning of another. It was also clear to him that his marriage to Emmy was over. He had finally found “his twin”, and nothing would stand in his way of the relationship he had wanted all of his life.

During the previous eighteen months Stieglitz and O’Keeffe had been writing to each other with increasing passion and seeing each other whenever possible. In early June, O’Keeffe moved to New York after Stieglitz promised he would provide her with a quiet studio where she could paint. They were inseparable from the moment she arrived, and within a month he took the first of many nude photographs of her. He chose to do this at his family’s apartment while his wife Emmy was away, but she returned while their session was still in progress. Emmy told him to stop seeing her or get out. Stieglitz did not hesitate; he left and immediately found a place in the city where he and O’Keeffe could live together. By mid-August when they visited Oaklawn “they were like two teenagers in love. Several times a day they would run up the stairs to their bedroom, so eager to make love that they would start taking their clothes off as they ran.”

Stieglitz filed for divorce almost immediately. Due to legal delays caused by Emmy and her brothers, it would be six more years before the divorce was finalized. During this period Stieglitz and O’Keeffe continued to live together. She was relatively free-spirited and out-going with Stieglitz and his friends, but she needed solitude for weeks or months at a time when she focused on painting or creating. This arrangement worked well with Stieglitz’s own lifestyle, and he used the times when she was away to concentrate on his photography and on his continued promotion of modern art.

One of the most important things that O’Keeffe provided for Stieglitz was the muse he had always wanted. He photographed O’Keeffe obsessively between 1918 and 1925 in what was the most prolific period in his entire life. During this period he produced more than 350 mounted prints of O’Keeffe that portrayed a wide range of her character, moods and beauty. He shot many close-up studies of parts of her body, especially her hands either isolated by themselves or near her face or hair. They remain one of the most dynamic and intimate records of a single individual in the history of art.

In the catalog for a 1921 show, Stieglitz made his famous declaration: “I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion. The search for Truth my obsession.” What is less known is that he conditioned this statement by following it with these words:

- “PLEASE NOTE: In the above STATEMENT the following, fast becoming “obsolete”, terms do not appear: ART, SCIENCE, BEAUTY, RELIGION, every ISM, ABSTRACTION, FORM, PLASTICITY, OBJECTIVITY, SUBJECTIVITY, OLD MASTERS, MODERN ART, PSYCHOANALYSIS, AESTHETICS, PICTORIAL PHOTOGRAPHY, DEMOCRACY, CEZANNE, “291”, PROHIBITION. The term TRUTH did creep in but it may be kicked out by any one.”

In the summer of 1923, O’Keeffe once again took off for the seclusion of the Southwest, and for a while Stieglitz was alone with Beck Strand at Lake George. He took a series of nude photos of her, and soon he became infatuated with her. They had a brief physical affair before O’Keeffe returned in the fall. O’Keeffe could tell what had happened, but since she did not see Stieglitz’s new lover as a serious threat to their relationship she let things pass. Six years later she would have her own affair with Beck Strand in New Mexico.

In 1924 Stieglitz’s divorce was finally approved by a judge, and within four months he and O’Keeffe married. It was a small, private ceremony at Marin’s house, and afterward the couple went back home. There was no reception, festivities or honeymoon. O’Keeffe said later that they married in order to help soothe the troubles of Stieglitz’s daughter Kitty, who at that time was being treated in a sanatorium for depression and hallucinations. The marriage did not seem to have any immediate effect on either Stieglitz or O’Keeffe; they both continued working on their individual projects as they had before. For the rest of their lives together, their relationship was, as biographer Benita Eisler characterized it, “a collusion … a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O’Keeffe was the principal agent of collusion in their union.”

In the coming years O’Keeffe would spend much of her time painting in New Mexico, while Stieglitz rarely left New York except for summers at Lake George. O’Keeffe later said “Stieglitz was a hypochondriac and couldn’t be more than 50 miles from a doctor.”

In 1927 a young woman named Dorothy Norman came to the gallery to look at works by Marin, and once again Stieglitz became infatuated with a much younger woman. She began volunteering for mundane tasks at the gallery, and soon she found she was returning Stieglitz’s attention. By the next year, when Stieglitz was sixty-four and she twenty-two, they both declared their love for each other.

For most of the past year O’Keeffe had been dealing with bouts of illness or secluded at Lake George painting, and she and Stieglitz had seen each other only intermittently. She knew of her husband’s interest in Norman but thought it was just another of his infatuations. Having struggled with artistic roadblocks for many months she felt she needed a major change of some sort, so when Mabel Dodge invited her to come to Santa Fe for the summer O’Keeffe told Stieglitz that she had to go in order to be able to create again. Stieglitz took advantage of her time away to begin photographing Norman, and he began teaching her the technical aspects of printing as well. Within a short time they became lovers, but even after their physical affair diminished a few years later they continued to work together whenever O’Keeffe was not around until Stieglitz died in 1946.

In the summer of 1946 Stieglitz suffered a fatal stroke. He remained in a coma long enough for O’Keeffe to finally return home. When she got to his hospital room Dorothy Norman was there with him. She left immediately, and O’Keeffe was with him when he died. According to his wishes, a simple funeral was held with only twenty of his closest friends and family in attendance. Stieglitz was cremated, and O’Keeffe and his niece Elizabeth Davidson took his ashes to Lake George. O’Keeffe never revealed exactly where she distributed them, saying only “I put him where he could hear the water.”

Gallery

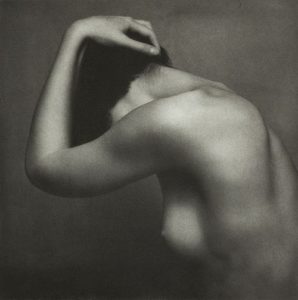

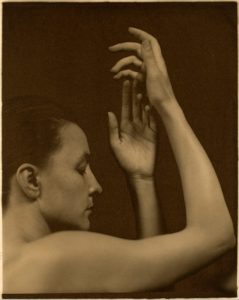

georgia o’keeffe

Georgia O’Keeffe

-

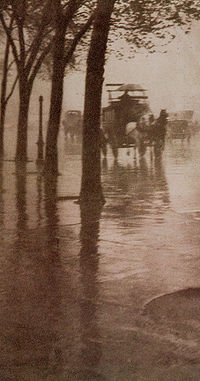

The Hand of Man, 1902

The Hand of Man, 1902 -

Katherine, 1905

Katherine, 1905 -

Miss S.R., 1905

Miss S.R., 1905 -

Dirigible, 1910

Dirigible, 1910 -

Old and New New York, 1910

Old and New New York, 1910 -

A Snapshot: Paris, 1911 (one of two with same title)

A Snapshot: Paris, 1911 (one of two with same title) -

A Snapshot: Paris, 1911 (one of two with same title)

A Snapshot: Paris, 1911 (one of two with same title) -

Ellen Koeniger, Lake George, 1916.

-

Georgia O’Keeffe, Hands, 1918

Georgia O’Keeffe, Hands, 1918

| E. M. Forster | |

|---|---|

E. M. Forster, by Dora Carrington

c. 1924–1925 |

|

And today is the birthday of E. M. Forster (Edward Morgan Forster, Marylebone, Middlesex, England 1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970 Coventry, Warwickshire, England); novelist, short story writer, essayist and librettist. Many of his novels examined class difference and hypocrisy in early 20th-century British society, notably A Room with a View (1908), Howards End (1910), and A Passage to India (1924), which brought him his greatest success. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 16 different years. Forster was a lifelong bachelor.

Prose

- I am the means and not the end. I am the food and not the life. Stand by yourself, as that boy has stood. I cannot save you. For poetry is a spirit; and they that would worship it must worship in spirit and in truth.

- “The Celestial Omnibus” (1911)

Where Angels Fear to Tread (1905)

- Romance only dies with life. No pair of pincers will ever pull it out of us. But there is a spurious sentiment which cannot resist the unexpected and the incongruous and the grotesque. A touch will loosen it, and the sooner it goes from us the better.

- Ch. 2

- A wonderful physical tie binds the parents to the children; and — by some sad, strange irony — it does not bind us children to our parents. For if it did, if we could answer their love not with gratitude but with equal love, life would lose much of its pathos and much of its squalor, and we might be wonderfully happy.

- Ch. 7

- I never expect anything to happen now, and so I am never disappointed. You would be surprised to know what my great events are. Going to the theatre yesterday, talking to you now — I don’t suppose I shall ever meet anything greater. I seem fated to pass through the world without colliding with it or moving it — and I’m sure I can’t tell you whether the fate’s good or evil. I don’t die — I don’t fall in love. And if other people die or fall in love they always do it when I’m just not there. You are quite right; life to me is just a spectacle, which — thank God, and thank Italy, and thank you — is now more beautiful and heartening than it has ever been before.

- Ch. 8

- This woman was a goddess to the end. For her no love could be degrading: she stood outside all degradation. This episode, which she thought so sordid, and which was so tragic for him, remained supremely beautiful. To such a height was he lifted, that without regret he could now have told her that he was her worshipper too. But what was the use of telling her? For all the wonderful things had happened.

“Thank you,” was all that he permitted himself. “Thank you for everything.”- Ch. 10

A Room with a View (1908)

- It is so difficult – at least, I find it difficult – to understand people who speak the truth.

- Ch.1

- There’s enough sorrow in the world, isn’t there, without trying to invent it.

- Ch. 2

- The kingdom of music is not the kingdom of this world; it will accept those whom breeding and intellect and culture have alike rejected. The commonplace person begins to play, and shoots into the empyrean without effort, whilst we look up, marvelling how he has escaped us, and thinking how we could worship him and love him, would he but transalate his visions into human words, and his experiences into human actions.

- Ch. 3

- Life is easy to chronicle, but bewildering to practice.

- Ch. 14

- It isn’t possible to love and to part. You will wish that it was. You can transmute love, ignore it, muddle it, but you can never pull it out of you. I know from experience that the poets are right: love is eternal.

- Ch. 19

Howards End (1910)

- He remembered his wife’s even goodness during thirty years. Not anything in detail — not courtship or early raptures —but just the unvarying virtue, that seemed to him a woman’s noblest quality. So many women are capricious, breaking into odd flaws of passion or frivolity. Not so his wife. Year after year, summer and winter, as bride and mother, she had been the same, he had always trusted her. Her tenderness! Her innocence! The wonderful innocence that was hers by the gift of God. Ruth knew no more of worldly wickedness and wisdom than did the flowers in her garden, or the grass in her field. Her idea of business — “Henry, why do people who have enough money try to get more money?” Her idea of politics — “I am sure that if the mothers of various nations could meet, there would be no more wars,” Her idea of religion — ah, this had been a cloud, but a cloud that passed. She came of Quaker stock, and he and his family, formerly Dissenters, were now members of the Church of England. The rector’s sermons had at first repelled her, and she had expressed a desire for “a more inward light,” adding, “not so much for myself as for baby” (Charles). Inward light must have been granted, for he heard no complaints in later years. They brought up their three children without dispute. They had never disputed.

She lay under the earth now. She had gone, and as if to make her going the more bitter, had gone with a touch of mystery that was all unlike her.- Ch. 11

- There’s nothing like a debate to teach one quickness. I often wish I had gone in for them when I was a youngster. It would have helped me no end.

- Ch. 15

- Personal relations are the important thing for ever and ever and not this outer life of telegrams and anger.

- Ch. 19

- She might yet be able to help him to the building of the rainbow bridge that should connect the prose in us with the passion. Without it we are meaningless fragments, half monks, half beasts, unconnected arches that have never joined into a man. With it love is born, and alights on the highest curve, glowing against the grey, sober against the fire. Happy the man who sees from either aspect the glory of these outspread wings. The roads of his soul lie clear, and he and his friends shall find easy-going.

- Ch. 22

- Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.

- Ch. 22

- In these English farms, if anywhere, one might see life steadily and see it whole, group in one vision its transitoriness and its eternal youth, connect — connect without bitterness until all men are brothers.

- Ch. 33

- Death destroys a man, but the idea of death saves him.

- Ch. 41

- “There are moments when I feel Howards End peculiarly our own.” “All the same, London’s creeping.” She pointed over the meadow–over eight or nine meadows, but at the end of them was a red rust. “You see that in Surrey and even Hampshire now,” she continued. “I can see it from the Purbeck Downs. And London is only part of something else, I’m afraid. Life’s going to be melted down, all over the world.” Margaret knew that her sister spoke truly. Howards End, Oniton, the Purbeck Downs, the Oderberge, were all survivals, and the melting-pot was being prepared for them. Logically, they had no right to be alive. One’s hope was in the weakness of logic. Were they possibly the earth beating time?

- Ch. 44

A Passage to India (1924)

- Adventures do occur, but not punctually.

- Ch. 3

- All invitations must proceed from heaven perhaps; perhaps it is futile for men to initiate their own unity, they do but widen the gulfs between them by the attempt.

- Ch. 4

- Most of life is so dull that there is nothing to be said about it, and the books and talks that would describe it as interesting are obliged to exaggerate, in the hope of justifying their own existence. Inside its cocoon of work or social obligation, the human spirit slumbers for the most part, registering the distinction between pleasure and pain, but not nearly as alert as we pretend. There are periods in the most thrilling day during which nothing happens, and though we continue to exclaim, “I do enjoy myself”, or , “I am horrified,” we are insincere.

- Ch. 14

- Pathos, piety, courage, — they exist, but are identical, and so is filth. Everything exists, nothing has value.

- Ch. 14

- ‘Why can’t we be friends now?’ said the other, holding him affectionately. ‘It’s what I want. It’s what you want.’ But the horses didn’t want it — they swerved apart: the earth didn’t want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temple, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they emerged from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn’t want it, they said in their hundred voices ‘No, not yet,’ and the sky said ‘No, not there.’

- Ch. 37

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 1 January – Happy New Year Y’all – impetus – photography by Alfred Stieglitz – birth of E. M. Forster"