Dear Zazie Lee, Here is the latest edition of The Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag. Do you know what it is to be one of two? Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

two together

in the same room

or time zones apart

nothin’ better

two, each half

of a whole

do you know

what it means

to be half

of a whole

do you know

how it feels

to not care

where you are goin’

as long as you are

one of two together

but two asunder

sleepin’ outta tune

i god, nothin’ worse

and why did the one,

every damn time,

follow the other

never hesitated

to board that train

not carin’ where

it was goin’

but once on board

inevitably, the lookin’

for the backdoor

countdown began

so whatcha gonna do

with a soi-disant poet

full of beauty and sorrow

© copyright 2017 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

Two

Just us two

Two bodies lyin’

Naked, exhausted

Two people livin’

Two people talkin’

Two people believin’

Two silver rings

Two different voices

Two ways to tell the story

Was there nothin’ I could do

To save you

When did we become so unhappy

How did we become disappointed

Our dreams disjointed,

Sleepin’ outta tune

Through all of the mistakes

Holdin’ each other in the archway

Through the thunderstorms

But no one could fix us no one could

There are no other witnesses

Just us two

The still gazes

Do not change in the shadows

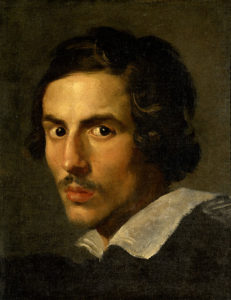

Today is the birthday of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (also Gianlorenzo or Giovanni Lorenzo; Naples; 7 December 1598 – 28 November 1680; Rome); painter, sculptor and architect. A major figure in the world of architecture and the leading sculptor of his age. He has been credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. In addition, he was a man of the theater: he wrote, directed and acted in plays. As architect and city planner, he designed both secular buildings and churches and chapels, as well as massive works combining both architecture and sculpture, including elaborate public fountains and funerary monuments and a whole series of temporary structures (in stucco and wood) for funerals and festivals.

Today is the birthday of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (also Gianlorenzo or Giovanni Lorenzo; Naples; 7 December 1598 – 28 November 1680; Rome); painter, sculptor and architect. A major figure in the world of architecture and the leading sculptor of his age. He has been credited with creating the Baroque style of sculpture. In addition, he was a man of the theater: he wrote, directed and acted in plays. As architect and city planner, he designed both secular buildings and churches and chapels, as well as massive works combining both architecture and sculpture, including elaborate public fountains and funerary monuments and a whole series of temporary structures (in stucco and wood) for funerals and festivals.

In the 1630s he engaged in an affair with a married woman named Costanza (wife of his workshop assistant, Matteo Bonucelli, also called Bonarelli) and sculpted a bust of her (now in the Bargello, Florence) during the height of their romance. She later had an affair with his younger brother, Luigi, who was Bernini’s right-hand man in his studio. When Gian Lorenzo found out about Costanza and his brother, he chased Luigi through the streets of Rome and into the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, threatening his life. To punish his unfaithful mistress, Bernini had a servant go to the house of Costanza, where the servant slashed her face several times with a razor. The servant was later jailed, and Costanza was jailed for adultery; Bernini himself was exonerated by the pope, even though he had committed a crime. Soon after, in May 1639, at age forty-one, Bernini wed a twenty-two-year-old Roman woman, Caterina Tezio, in an arranged marriage, under orders from Pope Urban. She bore him eleven children, including youngest son Domenico Bernini, who would later be his first biographer.

Gallery

“Sleeping Hermaphrodite” – The Louvre, Paris.

| Costanza |

|---|

|

| Willa Cather | |

|---|---|

Cather in 1912.

|

|

Today is the birthday of Willa Cather (Willa Sibert Cather; Gore, Virginia; December 7, 1873 – April 24, 1947 Manhattan); author who achieved recognition for her novels of frontier life on the High Plains, including O Pioneers! (1913), The Song of the Lark (1915), and My Ántonia (1918). In 1923 she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for One of Ours (1922), a novel set during World War I. Cather grew up in Virginia and Nebraska, and graduated from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. She lived and worked in Pittsburgh for ten years, supporting herself as a magazine editor and high school English teacher. At the age of 33 she moved to New York City, her primary home for the rest of her life.

Throughout Cather’s adult life, her most significant friendships were with women. These included her college friend Louise Pound; the Pittsburgh socialite Isabelle McClung, with whom Cather traveled to Europe and at whose Toronto home she stayed for prolonged visits; the opera singer Olive Fremstad; the pianist Yaltah Menuhin; and most notably, the editor Edith Lewis.

Cather’s relationship with Lewis began in the early 1900s. The two women lived together in a series of apartments in New York City from 1908 until Cather’s death in 1947. Cather selected Lewis as the literary trustee for her estate.

My Antonia (1918)

- There seemed to be nothing to see; no fences, no creeks or trees, no hills or fields. If there was a road, I could not make it out in the faint starlight. There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries are made.

- Book I, Ch. 1

- I kept as still as I could. Nothing happened. I did not expect anything to happen. I was something that lay under the sun and felt it, like the pumpkins, and I did not want to be anything more. I was entirely happy. Perhaps we feel like that when we die and become a part of something entire, whether it is sun and air, or goodness and knowledge. At any rate, that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great. When it comes to one, it comes as naturally as sleep.

- Book I, Ch. 2

- I ain’t got time to learn. I can work like mans now.

- Book 1, Ch. 17

- Winter lies too long in country towns; hangs on until it is stale and shabby, old and sullen. On the farm the weather was the great fact, and men’s affairs went on underneath it, as the streams creep under the ice. But in Black Hawk the scene of human life was spread out shrunken and pinched, frozen down to the bare stalk.

- Book II, Ch. 7

- On starlight nights I used to pace up and down those long, cold streets, scowling at the little, sleeping houses on either side, with their storm-windows and covered back porches. They were flimsy shelters, most of them poorly built of light wood, with spindle porch-posts horribly mutilated by the turning-lathe. Yet for all their frailness, how much jealousy and envy and unhappiness some of them managed to contain! The life that went on in them seemed to me made up of evasions and negations; shifts to save cooking, to save washing and cleaning, devices to propitiate the tongue of gossip. This guarded mode of existence was like living under a tyranny. People’s speech, their voices, their very glances, became furtive and repressed. Every individual taste, every natural appetite, was bridled by caution. The people asleep in those houses, I thought, tried to live like the mice in their own kitchens; to make no noise, to leave no trace, to slip over the surface of things in the dark.

- Book II, Ch. 12

- There were no clouds, the sun was going down in a limpid, gold-washed sky. Just as the lower edge of the red disk rested on the high fields against the horizon, a great black figure suddenly appeared on the face of the sun. We sprang to our feet, straining our eyes toward it. In a moment we realized what it was. On some upland farm, a plough had been left standing in the field. The sun was sinking just behind it. Magnified across the distance by the horizontal light, it stood out against the sun, was exactly contained within the circle of the disk; the handles, the tongue, the share — black against the molten red. There it was, heroic in size, a picture writing on the sun.

- Book II, Ch. 14

- “Jim,” she said earnestly, “if I was put down there in the middle of the night, I could find my way all over that little town; and along the river to the next town, where my grandmother lived. My feet remember all the little paths through the woods, and where the big roots stick out to trip you. I ain’t never forgot my own country.”

- Book II, Ch. 14

- Cleric said he thought Virgil, when he was dying at Brindisi, must have remembered that passage. After he had faced the bitter fact that he was to leave the ‘Aeneid’ unfinished, and had decreed that the great canvas, crowded with figures of gods and men, should be burned rather than survive him unperfected, then his mind must have gone back to the perfect utterance of the ‘Georgics,’ where the pen was fitted to the matter as the plough is to the furrow; and he must have said to himself, with the thankfulness of a good man, ‘I was the first to bring the Muse into my country.’

- Book III, Ch. 2

- Men are all right for friends, but as soon as you marry them they turn into cranky old fathers, even the wild ones. They begin to tell you what’s sensible and what’s foolish, and want you to stick at home all the time. I prefer to be foolish when I feel like it, and be accountable to nobody.

- Book III, Ch. 4

- She remembered home as a place where there were always too many children, a cross man and work piling up around a sick woman.

- Book III, Ch. 4

- The windy springs and the blazing summers, one after another, had enriched and mellowed that flat tableland; all the human effort that had gone into it was coming back in long, sweeping lines of fertility. The changes seemed beautiful and harmonious to me; it was like watching the growth of a great man or of a great idea. I recognized every tree and sandbank and rugged draw. I found that I remembered the conformation of the land as one remembers the modelling of human faces.

- Book IV, Ch. 3

- I think of you more often than of anyone else in this part of the world. I’d have liked to have you for a sweetheart, or a wife, or my mother or my sister — anything that a woman can be to a man. The idea of you is a part of my mind; you influence my likes and dislikes, all my tastes, hundreds of times when I don’t realize it. You really are a part of me.

- Book IV, Ch. 4

- Ain’t it wonderful, Jim, how much people can mean to each other?

- Bok IV, Ch. 4

- As we walked homeward across the fields, the sun dropped and lay like a great golden globe in the low west. While it hung there, the moon rose in the east, as big as a cart-wheel, pale silver and streaked with rose colour, thin as a bubble or a ghost-moon. For five, perhaps ten minutes, the two luminaries confronted each other across the level land, resting on opposite edges of the world.

In that singular light every little tree and shock of wheat, every sunflower stalk and clump of snow-on-the-mountain, drew itself up high and pointed; the very clods and furrows in the fields seemed to stand up sharply. I felt the old pull of the earth, the solemn magic that comes out of those fields at nightfall. I wished I could be a little boy again, and that my way could end there.- Book IV, Ch. 4

- In the course of twenty crowded years one parts with many illusions. I did not wish to lose the early ones. Some memories are realities, and are better than anything that can ever happen to one again.

- Book V, Ch. 1

- As I confronted her, the changes grew less apparent to me, her identity stronger. She was there, in the full vigour of her personality, battered but not diminished, looking at me, speaking to me in the husky, breathy voice I remembered so well.

- Book V, Ch. 1

- It was no wonder that her sons stood tall and straight. She was a rich mine of life, like the founders of early races.

- Book V, Ch. 1

- Whatever we had missed, we possessed together the precious, the incommunicable past.

- Book V, Ch. 3

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 7 December – two – art by Gian Lorenzo Bernini – birth of Willa Cather"