Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse. Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

“The pages are worn

but the story is strong.”

the music may be faint

but the melody is true

and it will save us…

so, solo pinot nights

suit just as well

as does cookin’ for one

tonight, foglie d’oliva pasta

with trapanese pesto sauce,

baked spicy dark meat chicken,

and dessert, dark chocolate cake

washed down with a little Sambuca

never miss a chance

to make the most

of a meal or a moment

alone or not

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

can there be

anything better

than cookin’ a fine meal

with a fine woman…

imagine me and you

in a kitchen

fixin’ this menu…

steak carpaccio

with fresh spinach

and arugula

red wine risotto

with fresh basil

and garlic

and for dessert

raspberry cream cupcakes

with a dark chocolate drizzle

and of course a bottle,

well maybe two,

of pinot noir

after that meal

and drinkin’

sex in a glass

and the way

we look at each other

yeah, the dishes

can wait till mornin’…

© copyright 2017 mac tag/cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

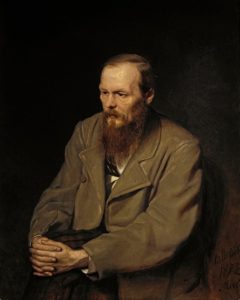

Today is the birthday of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (Moscow 11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881 Saint Petersburg); novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist and philosopher. Dostoevsky’s literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. Perhaps best know for his works Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). Dostoevsky’s oeuvre consists of 11 novels, three novellas, 17 short stories and numerous other works. In my opinion, he is one of the greatest psychologists in world literature. His 1864 novella Notes from Underground is considered to be one of the first works of existentialist literature.

Today is the birthday of Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (Moscow 11 November 1821 – 9 February 1881 Saint Petersburg); novelist, short story writer, essayist, journalist and philosopher. Dostoevsky’s literary works explore human psychology in the troubled political, social, and spiritual atmospheres of 19th-century Russia, and engage with a variety of philosophical and religious themes. Perhaps best know for his works Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1869), Demons (1872) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880). Dostoevsky’s oeuvre consists of 11 novels, three novellas, 17 short stories and numerous other works. In my opinion, he is one of the greatest psychologists in world literature. His 1864 novella Notes from Underground is considered to be one of the first works of existentialist literature.

Dostoevsky was introduced to literature at an early age through fairy tales and legends, and through books by Russian and foreign authors. His mother died in 1837 when he was 15, and around the same time, he left school to enter the Nikolayev Military Engineering Institute. After graduating, he worked as an engineer and briefly enjoyed a lavish lifestyle, translating books to earn extra money. In the mid-1840s he wrote his first novel, Poor Folk, which gained him entry into St. Petersburg’s literary circles. Arrested in 1849 for belonging to a literary group that discussed banned books critical of “Tsarist Russia”, he was sentenced to death but the sentence was commuted at the last moment. He spent four years in a Siberian prison camp, followed by six years of compulsory military service in exile. In the following years, Dostoevsky worked as a journalist, publishing and editing several magazines of his own and later A Writer’s Diary, a collection of his writings.

Dostoevsky was influenced by a wide variety of philosophers and authors including Pushkin, Gogol, Augustine, Shakespeare, Dickens, Balzac, Lermontov, Hugo, Poe, Plato, Cervantes, Herzen, Kant, Belinsky, Hegel, Schiller, Solovyov, Bakunin, Sand, Hoffmann, and Mickiewicz. His writings were widely read both within and beyond his native Russia and influenced an equally great number of later writers including Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anton Chekhov as well as philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre. His books have been translated into more than 170 languages. My favorite book of his is The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1877).

During a visit to Belikhov, Dostoevsky met Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva and fell in love. In 1856 Dostoevsky sent a letter through apologising for his activity in several utopian circles. As a result, he obtained the right to publish books and to marry, although he remained under police surveillance for the rest of his life. Maria married Dostoevsky in Semipalatinsk on 7 February 1857, even though she had initially refused his marriage proposal, stating that they were not meant for each other and that his poor financial situation precluded marriage. Their family life was unhappy and she found it difficult to cope with his seizures. Describing their relationship, he wrote: “Because of her strange, suspicious and fantastic character, we were definitely not happy together, but we could not stop loving each other; and the more unhappy we were, the more attached to each other we became”. They mostly lived apart.

in Paris, 1863

In 1864 Maria and his brother Mikhail died.

On 4 October 1866, Anna Snitkina started working as a stenographer on his novel The Gambler. A month later they became engaged.

In the Memoirs, Anna describes how Dostoevsky began his marriage proposal by outlining the plot of an imaginary new novel, as if he needed her advice on female psychology. In the story an old painter makes a proposal to a young girl whose name is Anya. Dostoevsky asked if it was possible for a girl so young and different in personality to fall in love with the painter. Anna answered that it was quite possible. Then he told Anna: “Put yourself in her place for a moment. Imagine I am the painter, I confessed to you and asked you to be my wife. What would you answer?” Anna said: “I would answer that I love you and I will love you forever”.

On 15 February 1867, the couple were married. Two months later they went abroad, where they remained for over four years (until July 1871).

The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1877)

- I am a ridiculous person. Now they call me a madman. That would be a promotion if it were not that I remain as ridiculous in their eyes as before. But now I do not resent it, they are all dear to me now, even when they laugh at me — and, indeed, it is just then that they are particularly dear to me. I could join in their laughter — not exactly at myself, but through affection for them, if I did not feel so sad as I look at them. Sad because they do not know the truth and I do know it. Oh, how hard it is to be the only one who knows the truth! But they won’t understand that. No, they won’t understand it.

- I

- I gave up caring about anything, and all the problems disappeared.

And it was after that that I found out the truth. I learnt the truth last November — on the third of November, to be precise — and I remember every instant since.- I

- The sky was horribly dark, but one could distinctly see tattered clouds, and between them fathomless black patches. Suddenly I noticed in one of these patches a star, and began watching it intently. That was because that star had given me an idea: I decided to kill myself that night.

- I

- It seemed clear to me that life and the world somehow depended upon me now. I may almost say that the world now seemed created for me alone: if I shot myself the world would cease to be at least for me. I say nothing of its being likely that nothing will exist for anyone when I am gone, and that as soon as my consciousness is extinguished the whole world will vanish too and become void like a phantom, as a mere appurtenance of my consciousness, for possibly all this world and all these people are only me myself.

- II

- Dreams, as we all know, are very queer things: some parts are presented with appalling vividness, with details worked up with the elaborate finish of jewellery, while others one gallops through, as it were, without noticing them at all, as, for instance, through space and time. Dreams seem to be spurred on not by reason but by desire, not by the head but by the heart, and yet what complicated tricks my reason has played sometimes in dreams, what utterly incomprehensible things happen to it!

- II

- Yes, I dreamed a dream, my dream of the third of November. They tease me now, telling me it was only a dream. But does it matter whether it was a dream or reality, if the dream made known to me the truth? If once one has recognized the truth and seen it, you know that it is the truth and that there is no other and there cannot be, whether you are asleep or awake. Let it be a dream, so be it, but that real life of which you make so much I had meant to extinguish by suicide, and my dream, my dream — oh, it revealed to me a different life, renewed, grand and full of power!

- II

- I suddenly dreamt that I picked up the revolver and aimed it straight at my heart — my heart, and not my head; and I had determined beforehand to fire at my head, at my right temple. After aiming at my chest I waited a second or two, and suddenly my candle, my table, and the wall in front of me began moving and heaving. I made haste to pull the trigger.

- III

- In dreams you sometimes fall from a height, or are stabbed, or beaten, but you never feel pain unless, perhaps, you really bruise yourself against the bedstead, then you feel pain and almost always wake up from it. It was the same in my dream. I did not feel any pain, but it seemed as though with my shot everything within me was shaken and everything was suddenly dimmed, and it grew horribly black around me. I seemed to be blinded, and it benumbed, and I was lying on something hard, stretched on my back; I saw nothing, and could not make the slightest movement.

- III

- On our earth we can only love with suffering and through suffering. We cannot love otherwise, and we know of no other sort of love. I want suffering in order to love. I long, I thirst, this very instant, to kiss with tears the earth that I have left, and I don’t want, I won’t accept life on any other!”

- III

- The children of the sun, the children of their sun — oh, how beautiful they were! Never had I seen on our own earth such beauty in mankind. Only perhaps in our children, in their earliest years, one might find, some remote faint reflection of this beauty. The eyes of these happy people shone with a clear brightness. Their faces were radiant with the light of reason and fullness of a serenity that comes of perfect understanding, but those faces were gay; in their words and voices there was a note of childlike joy. Oh, from the first moment, from the first glance at them, I understood it all! It was the earth untarnished by the Fall; on it lived people who had not sinned. They lived just in such a paradise as that in which, according to all the legends of mankind, our first parents lived before they sinned; the only difference was that all this earth was the same paradise. These people, laughing joyfully, thronged round me and caressed me; they took me home with them, and each of them tried to reassure me. Oh, they asked me no questions, but they seemed, I fancied, to know everything without asking, and they wanted to make haste to smoothe away the signs of suffering from my face.

- III

- Well, granted that it was only a dream, yet the sensation of the love of those innocent and beautiful people has remained with me for ever, and I feel as though their love is still flowing out to me from over there. I have seen them myself, have known them and been convinced; I loved them, I suffered for them afterwards. Oh, I understood at once even at the time that in many things I could not understand them at all … But I soon realised that their knowledge was gained and fostered by intuitions different from those of us on earth, and that their aspirations, too, were quite different. They desired nothing and were at peace; they did not aspire to knowledge of life as we aspire to understand it, because their lives were full. But their knowledge was higher and deeper than ours; for our science seeks to explain what life is, aspires to understand it in order to teach others how to love, while they without science knew how to live; and that I understood, but I could not understand their knowledge.

- IV

- They showed me their trees, and I could not understand the intense love with which they looked at them; it was as though they were talking with creatures like themselves. And perhaps I shall not be mistaken if I say that they conversed with them. Yes, they had found their language, and I am convinced that the trees understood them. They looked at all Nature like that — at the animals who lived in peace with them and did not attack them, but loved them, conquered by their love. They pointed to the stars and told me something about them which I could not understand, but I am convinced that they were somehow in touch with the stars, not only in thought, but by some living channel.

- IV

- They had no temples, but they had a real living and uninterrupted sense of oneness with the whole of the universe; they had no creed, but they had a certain knowledge that when their earthly joy had reached the limits of earthly nature, then there would come for them, for the living and for the dead, a still greater fullness of contact with the whole of the universe. They looked forward to that moment with joy, but without haste, not pining for it, but seeming to have a foretaste of it in their hearts, of which they talked to one another.

- IV

- They sang the praises of nature, of the sea, of the woods. They liked making songs about one another, and praised each other like children; they were the simplest songs, but they sprang from their hearts and went to one’s heart. And not only in their songs but in all their lives they seemed to do nothing but admire one another. It was like being in love with each other, but an all-embracing, universal feeling.

- IV

- Oh, everyone laughs in my face now, and assures me that one cannot dream of such details as I am telling now, that I only dreamed or felt one sensation that arose in my heart in delirium and made up the details myself when I woke up. And when I told them that perhaps it really was so, my God, how they shouted with laughter in my face, and what mirth I caused! Oh, yes, of course I was overcome by the mere sensation of my dream, and that was all that was preserved in my cruelly wounded heart; but the actual forms and images of my dream, that is, the very ones I really saw at the very time of my dream, were filled with such harmony, were so lovely and enchanting and were so actual, that on awakening I was, of course, incapable of clothing them in our poor language, so that they were bound to become blurred in my mind; and so perhaps I really was forced afterwards to make up the details, and so of course to distort them in my passionate desire to convey some at least of them as quickly as I could. But on the other hand, how can I help believing that it was all true? It was perhaps a thousand times brighter, happier and more joyful than I describe it. Granted that I dreamed it, yet it must have been real. You know, I will tell you a secret: perhaps it was not a dream at all!

- IV

- How it could come to pass I do not know, but I remember it clearly. The dream embraced thousands of years and left in me only a sense of the whole. I only know that I was the cause of their sin and downfall. Like a vile trichina, like a germ of the plague infecting whole kingdoms, so I contaminated all this earth, so happy and sinless before my coming. They learnt to lie, grew fond of lying, and discovered the charm of falsehood.

- V

- All became so jealous of the rights of their own personality that they did their very utmost to curtail and destroy them in others, and made that the chief thing in their lives. Slavery followed, even voluntary slavery; the weak eagerly submitted to the strong, on condition that the latter aided them to subdue the still weaker. Then there were saints who came to these people, weeping, and talked to them of their pride, of their loss of harmony and due proportion, of their loss of shame. They were laughed at or pelted with stones.

- V

- Alas! I always loved sorrow and tribulation, but only for myself, for myself; but I wept over them, pitying them. I stretched out my hands to them in despair, blaming, cursing and despising myself. I told them that all this was my doing, mine alone; that it was I had brought them corruption, contamination and falsity. I besought them to crucify me, I taught them how to make a cross. I could not kill myself, I had not the strength, but I wanted to suffer at their hands. I yearned for suffering, I longed that my blood should be drained to the last drop in these agonies. But they only laughed at me, and began at last to look upon me as crazy. They justified me, they declared that they had only got what they wanted themselves, and that all that now was could not have been otherwise. At last they declared to me that I was becoming dangerous and that they should lock me up in a madhouse if I did not hold my tongue. Then such grief took possession of my soul that my heart was wrung, and I felt as though I were dying; and then . . . then I awoke.

- V

- I go to spread the tidings, I want to spread the tidings — of what? Of the truth, for I have seen it, have seen it with my own eyes, have seen it in all its glory.

- V

- I have seen the truth; I have seen and I know that people can be beautiful and happy without losing the power of living on earth. I will not and cannot believe that evil is the normal condition of mankind. And it is just this faith of mine that they laugh at. But how can I help believing it? I have seen the truth — it is not as though I had invented it with my mind, I have seen it, seen it, and the living image of it has filled my soul for ever. I have seen it in such full perfection that I cannot believe that it is impossible for people to have it.

- V

- A dream! What is a dream? And is not our life a dream? I will say more. Suppose that this paradise will never come to pass (that I understand), yet I shall go on preaching it. And yet how simple it is: in one day, in one hour everything could be arranged at once! The chief thing is to love others like yourself, that’s the chief thing, and that’s everything; nothing else is wanted — you will find out at once how to arrange it all. And yet it’s an old truth which has been told and retold a billion times — but it has not formed part of our lives! The consciousness of life is higher than life, the knowledge of the laws of happiness is higher than happiness — that is what one must contend against. And I shall. If only everyone wants it, it can be arranged at once.

- V

| Paul Signac | |

|---|---|

Paul Signac with his palette, ca. 1883

|

|

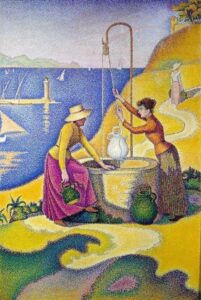

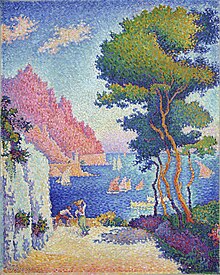

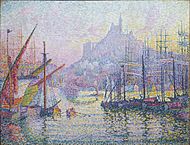

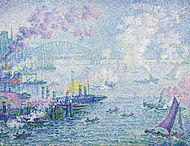

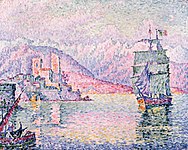

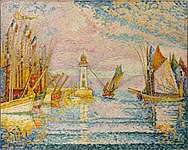

Today is the birthday of Paul Victor Jules Signac (Paris; 11 November 1863 – 15 August 1935 Paris); Neo-Impressionist painter who, working with Georges Seurat, helped develop the Pointillist style.

On 7 November 1892 Signac married Berthe Roblès at the town hall of the 18th arrondissement of Paris. Witnesses at the wedding were Alexandre Lemonier, Maximilien Luce, Camille Pissarro and Georges Lecomte. In November 1897, the Signacs moved to a new apartment in the Castel Béranger, built by Hector Guimard. In December of the same year, they acquired a house in Saint-Tropez called La Hune, where he had a studio constructed.

In September 1913, Signac rented a house at Antibes, where he settled with Jeanne Selmersheim-Desgrange. Signac had left La Hune as well as the Castel Beranger apartment to Berthe. They remained friends for the rest of his life.

Signac died from septicemia at the age of 71. His body was cremated and buried three days later, on 18 August, at the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Gallery

Femmes au puits, 1892.

-

Road to Gennevilliers, 1883, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

-

Comblat le Chateau. Le Pré. 1886, Dallas Museum of Art

-

Cassis, Cap Lombard, Opus 196, 1889, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

-

Golfe-Juan, ca. 1896, Worcester Art Museum

-

Grand Canal (Venice), 1905, Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio

-

Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde (La Bonne-Mère) Marseilles, 1905–06, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Port of Rotterdam, 1907, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

-

The Pine Tree at Saint Tropez, 1909, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

-

Antibes, 1911, Albertina, Vienna

-

Antibes le soir, 1914, Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

-

Entrée du port de la Rochelle, 1921, oil on canvas, 130.5 x 162 cm (51.4 × 63.8 in), Musée d’Orsay

-

Le phare, Groix, 1925, oil on canvas, 74 × 92.4 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

| Édouard Vuillard | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1889, oil on canvas

|

|

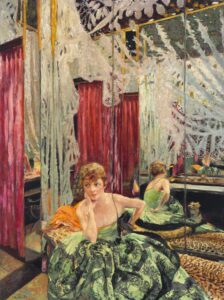

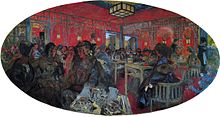

Today is the birthday of Jean-Édouard Vuillard (Cuiseaux, Saône-et-Loire; 11 November 1868 – 21 June 1940 La Baule, Loire-Atlantique); painter and printmaker associated with the Nabis.

Gallery

Jane Renouardt

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 11 November – pinot night – birth of Fyodor Dostoevsky – art by Paul Signac & Édouard Vuillard"