| Georgia O’Keeffe |

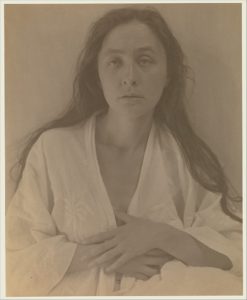

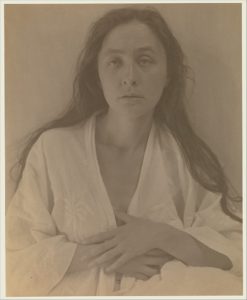

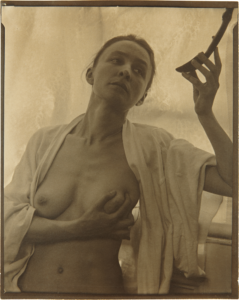

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz

|

|

|

Today is the birthday of Georgia Totto O’Keeffe (Town of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin; November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986 Santa Fe, New Mexico); artist. She was best known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O’Keeffe has been recognized as the “Mother of American modernism”.

O’Keefe took a job as head of the art department at West Texas State Normal College from late 1916 to February 1918, the fledgling West Texas A&M University in Canyon just south of Amarillo. While there, she often visited the Palo Duro Canyon, making its forms a subject in her work.

Alfred Stieglitz organized O’Keeffe’s first solo show at his 291 art gallery in April 1917, which included oil paintings and watercolors completed in Texas.

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe corresponded frequently beginning in 1916 and, in June 1918, she accepted his invitation to move to New York to devote all of her time to her work. The two were in love and, shortly after her arrival, they began living together, even though Stieglitz was married and 23 years her senior. That year, Stieglitz first took O’Keeffe to his family home at the village of Lake George in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. They spent part of every year there until 1929, when O’Keeffe spent the first of many summers painting in New Mexico. In 1924, Stieglitz’s divorce was approved by a judge and, within four months, he and O’Keeffe married. It was a small, private ceremony at John Marin’s house, and afterward the couple went back home. There was no reception, festivities, or honeymoon. After the marriage, they both continued working on their individual projects as they had before. For the rest of their lives together, their relationship was, as biographer Benita Eisler characterized it,

a collusion … a system of deals and trade-offs, tacitly agreed to and carried out, for the most part, without the exchange of a word. Preferring avoidance to confrontation on most issues, O’Keeffe was the principal agent of collusion in their union.

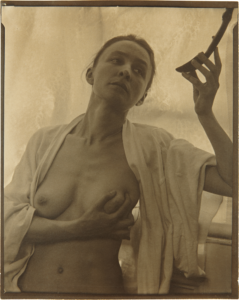

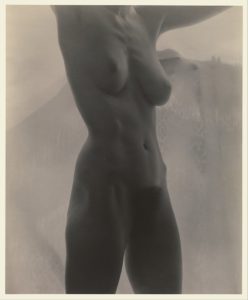

Stieglitz started photographing O’Keeffe when she visited him in New York City to see her 1917 exhibition. By 1937, when he retired from photography, he had made more than 350 portraits of her. Most of the more erotic photographs were made in the 1910s and early 1920s. In February 1921, forty-five of Stieglitz’s photographs were exhibited in a retrospective exhibition at the Anderson Galleries, including many of O’Keeffe, some of which depicted her in the nude. It created a public sensation. She once made a remark to Pollitzer about the nude photographs which may be the best indication of O’Keeffe’s ultimate reaction to being their subject: “I felt somehow that the photographs had nothing to do with me personally.” In 1978, she wrote about how distant from them she had become: “When I look over the photographs Stieglitz took of me-some of them more than sixty years ago—I wonder who that person is. It is as if in my one life I have lived many lives. If the person in the photographs were living in this world today, she would be quite a different person—but it doesn’t matter—Stieglitz photographed her then.”

By 1929, O’Keeffe acted on her increasing need to find a new source of inspiration for her work and to escape summers at Lake George, where she was surrounded by the Stieglitz family and their friends. O’Keeffe had considered finding a studio separate from Lake George in upstate New York and had also thought about spending the summer in Europe, but opted instead to travel to Santa Fe, with her friend Rebecca Strand. The two set out by train in May 1929 and soon after their arrival, Mabel Dodge Luhan moved them to her house in Taos and provided them with studios. O’Keeffe went on many pack trips exploring the rugged mountains and deserts of the region that summer and later visited the nearby D. H. Lawrence Ranch, where she completed her now famous oil painting, The Lawrence Tree, currently owned by the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut.

Between 1929 and 1949, O’Keeffe spent part of nearly every year working in New Mexico. She collected rocks and bones from the desert floor and made them and the distinctive architectural and landscape forms of the area subjects in her work. She also went on several camping trips with friends, visiting important sites in the Southwest, and in 1961, she and others, including photographers Eliot Porter and Todd Webb, went on a rafting trip down the Colorado River about Glen Canyon, Utah.

In August of 1934, she visited Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú, for the first time and decided to live there. In 1940, she moved into a house on the ranch property. The varicolored cliffs of Ghost Ranch inspired some of her most famous landscapes. In 1977, O’Keeffe wrote: “[the] cliffs over there are almost painted for you—you think—until you try to paint them.” Among guests to visit her at the ranch over the years were Charles and Anne Lindbergh, singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, poet Allen Ginsberg, and photographer Ansel Adams.

Known as a loner, O’Keeffe explored the land she loved often in her Ford Model A, which she purchased and learned to drive in 1929. She often talked about her fondness for Ghost Ranch and Northern New Mexico, as in 1943, when she explained: “Such a beautiful, untouched lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the ‘Faraway’. It is a place I have painted before … even now I must do it again.”

As early as 1936, O’Keeffe developed an intense interest in what is called the “Black Place”, which was about 150 miles west of her Ghost Ranch house. She made an extensive series of paintings of this site in the 1940s. O’Keeffe said that the Black Place resembled “a mile of elephants with gray hills and white sand at their feet.” At times the wind was so strong when she was painting there that she had trouble keeping her canvas on the easel. When the heat from the sun became intense, she crawled under her car for shade. The Black Place still remains remote and uninhabited.

She also made paintings of the “White Place”, a white rock formation located near her Abiquiú house. In 1945, O’Keeffe bought a second house, an abandoned hacienda in Abiquiú, some 18 miles (26 km) south of Ghost Ranch.

Shortly after O’Keeffe arrived for the summer in New Mexico in 1946, Stieglitz suffered a cerebral thrombosis. She flew to New York to be with him. He died on July 13, 1946. She buried his ashes at Lake George. She spent the next three years mostly in New York settling his estate, and moved permanently to New Mexico in 1949.

O’Keeffe met photographer Todd Webb in the 1940s. After his move to New Mexico in 1961, he often made photographs of her, as did numerous other important American photographers, who consistently presented O’Keeffe as a “loner, a severe figure and self-made person.” While O’Keeffe was known to have a “prickly personality”, Webb’s photographs portray her with a kind of “quietness and calm” suggesting a relaxed friendship, and revealing new contours of O’Keeffe’s character.

In 1972, O’Keeffe’s eyesight was compromised by macular degeneration, leading to the loss of central vision and leaving her with only peripheral vision. She stopped oil painting without assistance in 1972, but continued working in pencil and charcoal until 1984.

O’Keeffe became increasingly frail in her late 90s. She moved to Santa Fe in 1984, where she died at the age of 98. In accordance with her wishes, her body was cremated and her ashes were scattered to the wind at the top of Pedernal Mountain, over her beloved “faraway”.

Gallery

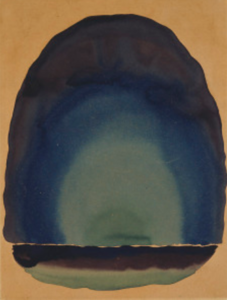

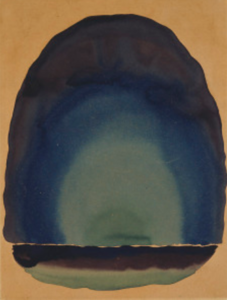

Blue and Green Music, 1921, oil on canvas

Stieglitz photograph of O’Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors, 1918

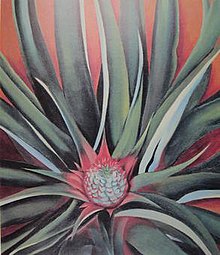

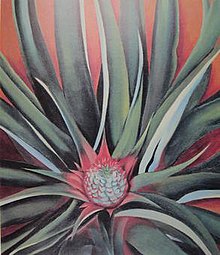

Pineapple Bud, 1939, oil on canvas

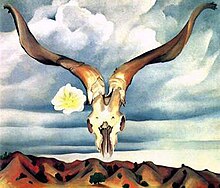

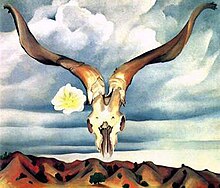

Ram’s Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills, 1935, The Brooklyn Museum

O’Keeffe’s “White Place,” the Plaza Blanca cliffs and badlands near Abiquiú

Cerro Pedernal, viewed from Ghost Ranch. This was a favorite subject for O’Keeffe, who once said, “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it”

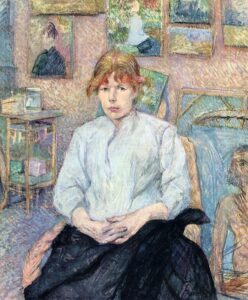

Georgia O’Keeffe, platinum print, 1920

My Shanty, Lake George, 1922, oil on canvas, 20 × 27 1/8 in., The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

-

Untitled – vase of flowers, 1903–1905, watercolor on paper, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

-

Red Canna, 1915, watercolor on paper, 19.4 by 13.0 inches (49.2 cm × 33.0 cm), Yale University Art Gallery

-

Drawing No. 2 – Special, 1915, charcoal on laid paper, 23.6 by 18.2 inches (60 cm × 46.3 cm), National Gallery of Art

-

Blue #1, 1916, watercolor and graphite on paper, Brooklyn Museum

-

Sunrise, 1916, watercolor on paper

-

No. 8 – Special, 1916, Whitney Museum of Art

-

Light Coming on the Plains No. II, 1917, watercolor on newsprint paper, 11+7⁄8 by 8+7⁄8 inches (30 cm × 23 cm), Amon Carter Museum of American Art

-

Series 1, No. 8, 1918, oil-painting on canvas, 20.0 by 16.0 inches (50.8 cm × 40.6 cm), Lenbachhaus, Munich

-

Red Canna, 1919, oil on board, High Museum of Art, Atlanta

-

A Storm, 1922, pastel on paper, mounted on illustration board, 18.3 by 24.4 inches (46.4 cm × 61.9 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art

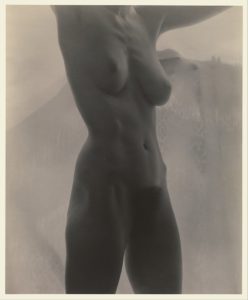

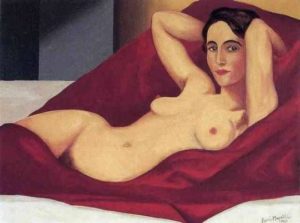

Torso by Stieglitz

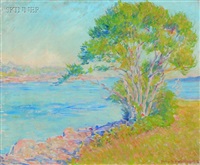

Today, a new feature on TLC; on occasion, I will feature original photography or artwork that I have created for you. This is Lake Francis Case in South Dakota. I took this picture in October just after first light. I camped in this spot overnight. As you know, this is right where I like to be; in the middle of nowhere with not another soul for miles. Hope you enjoy the view as much as I did.

Today, a new feature on TLC; on occasion, I will feature original photography or artwork that I have created for you. This is Lake Francis Case in South Dakota. I took this picture in October just after first light. I camped in this spot overnight. As you know, this is right where I like to be; in the middle of nowhere with not another soul for miles. Hope you enjoy the view as much as I did.

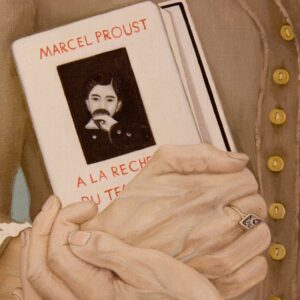

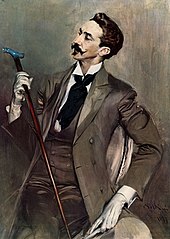

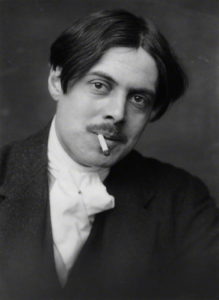

Today is the birthday of André Paul Guillaume Gide (Paris 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951 Paris); author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide’s career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anti-colonialism between the two World Wars. The New York Times described him as “France’s greatest contemporary man of letters” and “judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti.”

Today is the birthday of André Paul Guillaume Gide (Paris 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951 Paris); author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide’s career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anti-colonialism between the two World Wars. The New York Times described him as “France’s greatest contemporary man of letters” and “judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti.”

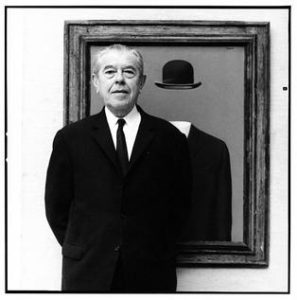

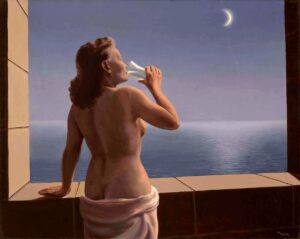

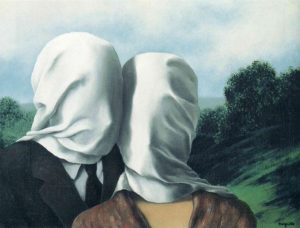

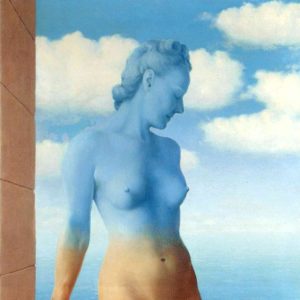

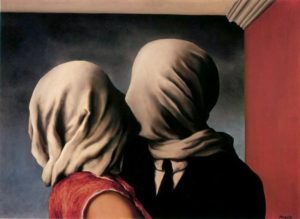

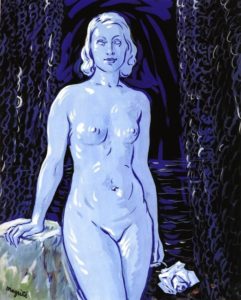

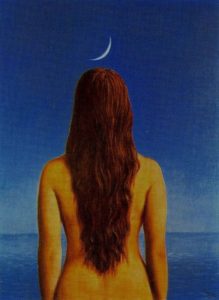

Today is the birthday of René François Ghislain Magritte (Lessines, Belgium; 21 November 1898 – 15 August 1967 Brussels); surrealist artist. He became well known for creating a number of witty and thought-provoking images. Often depicting ordinary objects in an unusual context, his work is known for challenging observers’ preconditioned perceptions of reality. His imagery has influenced Pop art, minimalist and conceptual art.

Today is the birthday of René François Ghislain Magritte (Lessines, Belgium; 21 November 1898 – 15 August 1967 Brussels); surrealist artist. He became well known for creating a number of witty and thought-provoking images. Often depicting ordinary objects in an unusual context, his work is known for challenging observers’ preconditioned perceptions of reality. His imagery has influenced Pop art, minimalist and conceptual art.

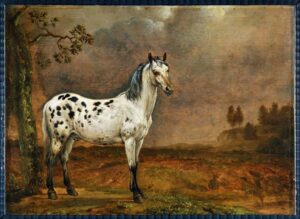

Today is the birthday of Paulus Potter (Enkhuizen, Netherlands 20 November 1625 (baptised) – 17 January 1654 (buried) Amsterdam); painter who specialized in animals within landscapes, usually with a low vantage point.

Today is the birthday of Paulus Potter (Enkhuizen, Netherlands 20 November 1625 (baptised) – 17 January 1654 (buried) Amsterdam); painter who specialized in animals within landscapes, usually with a low vantage point.

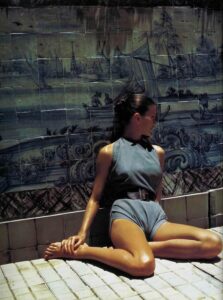

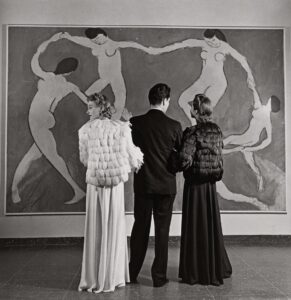

And today is the birthday of Louise Dahl-Wolfe (Louise Emma Augusta Dahl; San Francisco; November 19, 1895 – December 11, 1989 Allendale, New Jersey); photographer. She is known primarily for her work for Harper’s Bazaar, in association with fashion editor Diana Vreeland.

And today is the birthday of Louise Dahl-Wolfe (Louise Emma Augusta Dahl; San Francisco; November 19, 1895 – December 11, 1989 Allendale, New Jersey); photographer. She is known primarily for her work for Harper’s Bazaar, in association with fashion editor Diana Vreeland.

the sense that after all

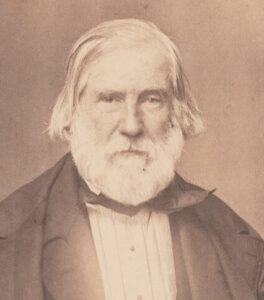

the sense that after all Today is the birthday of Charles Lock Eastlake (Plymouth, Devon, England 17 November 1793 – 24 December 1865 Pisa, Italy); painter, gallery director, collector and writer of the 19th century. After a period as keeper, he was the first director of the National Gallery.

Today is the birthday of Charles Lock Eastlake (Plymouth, Devon, England 17 November 1793 – 24 December 1865 Pisa, Italy); painter, gallery director, collector and writer of the 19th century. After a period as keeper, he was the first director of the National Gallery.

Today is the birthday of Francis Danby (County Wexford, Ireland 16 November 1793 – 9 February 1861 Exmouth, England); painter of the Romantic era.

Today is the birthday of Francis Danby (County Wexford, Ireland 16 November 1793 – 9 February 1861 Exmouth, England); painter of the Romantic era.