Dear Zazie, Here is today’s Lovers’ Chronicle from Mac Tag dedicated to his muse.

Rhett

The Lovers’ Chronicle

Dear Muse,

© copyright 2020 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

© copyright 2019 mac tag/cowboy Coleridge all rights reserved

perhaps my best, shortest poem…

thankful

for you

……

who that cares so much…

smile at the thoughts

walkin’ forth one evenin’

hand in hand, an ideal life

fed from within, soar

with illimitable satisfaction

anyone observin’

sees the change,

the vivid glances,

the subtlety

of touches,

the freshness

of sunlit mornin’

© copyright 2018 mac tag/cowboy coleridge all rights reserved

Today, a new feature on TLC; on occasion, I will feature original photography or artwork that I have created for you. This is Lake Francis Case in South Dakota. I took this picture in October just after first light. I camped in this spot overnight. As you know, this is right where I like to be; in the middle of nowhere with not another soul for miles. Hope you enjoy the view as much as I did.

Today, a new feature on TLC; on occasion, I will feature original photography or artwork that I have created for you. This is Lake Francis Case in South Dakota. I took this picture in October just after first light. I camped in this spot overnight. As you know, this is right where I like to be; in the middle of nowhere with not another soul for miles. Hope you enjoy the view as much as I did.

| George Eliot | |

|---|---|

Aged 30 by the Swiss artist Alexandre Louis François d’Albert Durade (1804–86)

|

|

Today is the birthday of Mary Ann Evans (Nuneaton, Warwickshire 22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880 Chelsea, Middlesex; alternatively “Mary Anne” or “Marian”), known by her pen name George Eliot; novelist, poet, journalist, translator and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She is the author of seven novels, including Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Felix Holt, the Radical (1866), Middlemarch (1871–72), and Daniel Deronda (1876). Most of her novels are set in provincial England and known for their realism and psychological insight. She used a male pen name, she said, to ensure that her works would be taken seriously. Female authors were published under their own names during Eliot’s life, but she wanted to escape the stereotype of women writing only lighthearted romances. She also wished to have her fiction judged separately from her already extensive and widely known work as an editor and critic. An additional factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny and to prevent scandals attending her relationship with the married George Henry Lewes, with whom she lived for over 20 years.

The philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes (1817–78) met Evans in 1851, and by 1854 they had decided to live together. Lewes was already married to Agnes Jervis. They had an open marriage. Because Lewes allowed himself to be falsely named as the father on the birth certificates of Jervis’s illegitimate children, he was considered to be complicit in adultery, and therefore he was not legally able to divorce her. In July 1854, Lewes and Evans travelled to Weimar and Berlin together for the purpose of research.

The trip to Germany also served as a honeymoon for Evans and Lewes, and they now considered themselves married, with Evans calling herself Mary Ann Evans Lewes, and referring to Lewes as her husband. It was not unusual for men and women in Victorian society to have affairs; it was the lack of discretion and their public admission of the relationship which created accusations of polygamy and earned them the moral disapproval of English society.

On 16 May 1880 Eliot courted controversy once more by marrying John Cross, a man twenty years her junior, and again changing her name, this time to Mary Anne Cross. While the couple was honeymooning in Venice, Cross, in a fit of depression, jumped from the hotel balcony into the Grand Canal. He survived, and the newlyweds returned to England. They moved to a new house in Chelsea, but Eliot fell ill with a throat infection. This, coupled with the kidney disease she had been afflicted with for several years, led to her death on 22 December 1880 at the age of 61.

Eliot was not buried in Westminster Abbey because of her denial of the Christian faith and her unconventional life with Lewes. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery (East), Highgate, London, in the area reserved for religious dissenters and agnostics, beside the love of her life, George Lewes. In 1980, on the centenary of her death, a memorial stone was established for her in the Poets’ Corner.

Verse

May I Join the Choir Invisible (1867)

- O may I join the choir invisible

Of those immortal dead who live again

In minds made better by their presence; live

In pulses stirred to generosity,

In deeds of daring rectitude, in scorn

For miserable aims that end with self,

In thoughts sublime that pierce the night like stars,

And with their mild persistence urge men’s search

To vaster issues.

- So to live is heaven:

To make undying music in the world,

Breathing a beauteous order that controls

With growing sway the growing life of man.

- This is life to come, —

Which martyred men have made more glorious

For us who strive to follow. May I reach

That purest heaven, — be to other souls

The cup of strength in some great agony,

Enkindle generous ardor, feed pure love,

Beget the smiles that have no cruelty,

Be the sweet presence of a good diffused,

And in diffusion ever more intense!

So shall I join the choir invisible

Whose music is the gladness of the world.

Middlemarch (1871)

- Who that cares much to know the history of man, and how the mysterious mixture behaves under the varying experiments of Time, has not dwelt, at least briefly, on the life of Saint Theresa, has not smiled with some gentleness at the thought of the little girl walking forth one morning hand-in-hand with her still smaller brother, to go and seek martyrdom in the country of the Moors? Out they toddled from rugged Avila, wide-eyed and helpless-looking as two fawns, but with human hearts, already beating to a national idea; until domestic reality met them in the shape of uncles, and turned them back from their great resolve. That child-pilgrimage was a fit beginning. Theresa’s passionate, ideal nature demanded an epic life: what were many-volumed romances of chivalry and the social conquests of a brilliant girl to her? Her flame quickly burned up that light fuel; and, fed from within, soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self. She found her epos in the reform of a religious order.

- Prelude

- That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago, was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity; perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into oblivion.

- Prelude

- Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women: if there were one level of feminine incompetence as strict as the ability to count three and no more, the social lot of women might be treated with scientific certitude. Meanwhile the indefiniteness remains, and the limits of variation are really much wider than any one would imagine from the sameness of women’s coiffure and the favorite love-stories in prose and verse. Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasily among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary-footed kind. Here and there is born a Saint Theresa, foundress of nothing, whose loving heart-beats and sobs after an unattained goodness tremble off and are dispersed among hindrances, instead of centring in some long-recognizable deed.

- Prelude

- Miss Brooke had that kind of beauty which seems to be thrown into relief by poor dress.

- First lines.

- ‘I suppose a woman is never in love with any one she has always known— ever since she can remember; as a man often is. It is always some new fellow who strikes a girl.’

- When Mrs. Casaubon was announced he started up as from an electric shock, and felt a tingling at his fingerends. Any one observing him would have seen a change in his complexion, in the adjustment of his facial muscles, in the vividness of his glance, which might have made them imagine that every molecule in his body had passed the message of a magic touch. And so it had. For effective magic is transcendent nature; and who shall measure the subtlety of those touches which convey the quality of soul as well as body, and make a man’s passion for one woman differ from his passion for another as joy in the morning light over valley and river and white mountain-top differs from joy among Chinese lanterns and glass panels? Will, too, was made of very impressible stuff. The bow of a violin drawn near him cleverly, would at one stroke change the aspect of the world for him, and his point of view shifted— as easily as his mood. Dorothea’s entrance was the freshness of morning.

- But what we call our despair is often only the painful eagerness of unfed hope.

- She nursed him, she read to him, she anticipated his wants, and was solicitous about his feelings; but there had entered into the husband’s mind the certainty that she judged him, and that her wifely devotedness was like a penitential expiation of unbelieving thoughts—was accompanied with a power of comparison by which himself and his doings were seen too luminously as a part of things in general. His discontent passed vaporlike through all her gentle loving manifestations, and clung to that unappreciative world which she had only brought nearer to him.

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

- Last lines

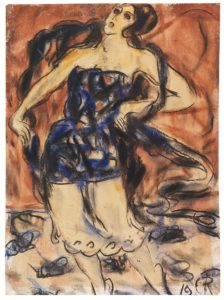

Rohlfs, self-portrait (1918)

In 1901 Rohlfs left Weimar for Hagen, where through the architect Henri van der Velde got to know the art collector Karl Ernst Osthaus who offered him a studio in an estate which would become the Museum Folkwang. Rohlfs was the first artist to begin to work there. Meetings with Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde and the experience of seeing the works of Vincent van Gogh inspired him to move towards the expressionist style, in which he would work for the rest of his career.

In 1908, at the age of 60, he made his first prints after seeing an exhibition of works by the expressionist group Die Brücke. He went on to make 185 in total, almost all woodcuts or linocuts. He lived in Munich and the Tyrol in 1910–12, before returning to Hagen. The outbreak of World War I worried Rohlfs such, that for some time he felt unable to paint. In rare instances he experimented with heavily hand-coloring his prints, onto the verge of painting and sometimes well after they were made, as in his 1919 recoloring of the prior year’s Der Gefangene.

In May 1922 he attended the International Congress of Progressive Artists and signed the “Founding Proclamation of the Union of Progressive International Artists”. In 1937 the Nazis expelled him from the Prussian Academy of Arts, condemned his work as degenerate, and removed his works from public collections. Seventeen of his paintings were exhibited in the Degenerate Art Exhibition in 1937.

Gallery

Dancing around the ball of the sun

-

Hilly landscape in late autumn, 1900

-

Collegiate Church of St. Patroclus in Soest, 1912, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

-

Landscape vision, 1912, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

-

The temptation of Christ, 1914, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

-

Sternbrücke in Weimar., (ca. 1917)

Dancer

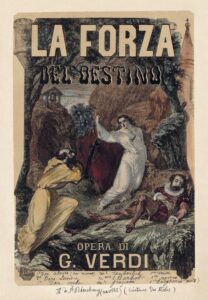

c. 1870 poster by Charles Lecocq

On this day in 1862, La forza del destino (The Power of Fate, or The Force of Destiny); an Italian opera by Giuseppe Verdi had its premiere in the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre of Saint Petersburg, Russia. The libretto was written by Francesco Maria Piave based on a Spanish drama, Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino (1835), by Ángel de Saavedra, 3rd Duke of Rivas, with a scene adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s Wallensteins Lager.

La forza del destino is frequently performed, and there have been a number of complete recordings. In addition, the overture (to the revised version of the opera) is part of the standard repertoire for orchestras, often played as the opening piece at concerts.

1860s postcard showing Act IV.

Enrico Caruso, Jose Mardones and Rosa Ponselle in a 1918 Metropolitan Opera performance.

Forza is an opera that many old school Italian singers felt was “cursed” and brought bad luck. The superstitious Luciano Pavarotti avoided the part of Alvaro.

On 4 March 1960 at the Metropolitan Opera, in a performance of La Forza del Destino with Renata Tebaldi and tenor Richard Tucker, the American baritone Leonard Warren was about to launch into the vigorous cabaletta to Don Carlo’s Act 3 aria, which begins “Morir, tremenda cosa” (“to die, a momentous thing”). Warren either simply went silent and fell face-forward to the floor, or started coughing and gasping, and cried out “Help me, help me!” before falling to the floor, remaining motionless. A few minutes later he was pronounced dead of a massive cerebral hemorrhage, and the rest of the performance was canceled. Warren was only 48.

The “Curse” prompted singers and others to do strange things to fend off possible bad luck. The great Italian tenor Franco Corelli was rumored to have held on to his groin during some of his performances of the opera as “protection.”

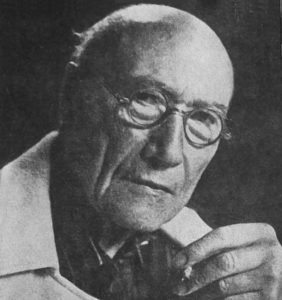

Today is the birthday of André Paul Guillaume Gide (Paris 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951 Paris); author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide’s career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anti-colonialism between the two World Wars. The New York Times described him as “France’s greatest contemporary man of letters” and “judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti.”

Today is the birthday of André Paul Guillaume Gide (Paris 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951 Paris); author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide’s career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anti-colonialism between the two World Wars. The New York Times described him as “France’s greatest contemporary man of letters” and “judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti.”

Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide exposes to public view the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality, split apart by a straitlaced traducing of education and a narrow social moralism. Gide’s work can be seen as an investigation of freedom and empowerment in the face of moralistic and puritanical constraints, and centres on his continuous effort to achieve intellectual honesty. His self-exploratory texts reflect his search of how to be oneself, including owning one’s sexual nature, without betraying one’s values. His political activity is shaped by the same ethos, as indicated by his repudiation of communism after his 1936 voyage to the USSR.

- La sagesse n’est pas dans la raison, mais dans l’amour.

- Wisdom comes not from reason but from love.

- Les Nourritures Terrestres [Fruits of the Earth] (1897), book I

- Wisdom comes not from reason but from love.

- …que toute émotion sache te devenir une ivresse. Si ce que tu manges ne te grise pas, c’est que tu n’avais pas assez faim.

- Let every emotion be capable of becoming an intoxication to you. If what you eat fails to make you drunk, it is because you are not hungry enough.

- Les Nourritures Terrestres (1897)

- Let every emotion be capable of becoming an intoxication to you. If what you eat fails to make you drunk, it is because you are not hungry enough.

- Ce qu’un autre aurait aussi bien fait que toi, ne le fais pas. Ce qu’un autre aurait aussi bien dit que toi, ne le dis pas, — aussi bien écrit que toi, ne l’écris pas. Ne t’attache en toi qu’à ce que tu sens qui n’est nulle part ailleurs qu’en toi-même, et crée de toi, impatiemment ou patiemment, ah! le plus irremplaçable des êtres.

- What another would have done as well as you, do not do it. What another would have said as well as you, do not say it; what another would have written as well, do not write it. Be faithful to that which exists nowhere but in yourself — and thus make yourself indispensable.

- Les Nourritures Terrestres (1897), Envoi

- What another would have done as well as you, do not do it. What another would have said as well as you, do not say it; what another would have written as well, do not write it. Be faithful to that which exists nowhere but in yourself — and thus make yourself indispensable.

- Le péché, c’est ce qui obscurcit l’âme.

- Sin is whatever obscures the soul.

- La Symphonie Pastorale (1919)

- Sin is whatever obscures the soul.

- On ne découvre pas de terre nouvelle sans consentir à perdre de vue, d’abord et longtemps, tout rivage.

- One doesn’t discover new lands without consenting to lose sight, for a very long time, of the shore.

- Les faux-monnayeurs [The Counterfeiters] (1925)

- One doesn’t discover new lands without consenting to lose sight, for a very long time, of the shore.

- C’est avec de beaux sentiments qu’on fait de la mauvaise littérature.

- It is with noble sentiments that bad literature gets written.

- Letter to François Mauriac (1929)

- It is with noble sentiments that bad literature gets written.

- Croyez ceux qui cherchent la vérité, doutez de ceux qui la trouvent; doutez de tout, mais ne doutez pas de vous-même.

- Believe those who seek the truth, doubt those who find it; doubt all, but do not doubt yourself.

- Gallimard, ed. (1952), Ainsi soit-il; ou, Les Jeux sont faits, p. 174

- Toutes choses sont dites déjà; mais comme personne n’écoute, il faut toujours recommencer.

- Everything has been said before, but since nobody listens we have to keep going back and beginning all over again.

- Le Traité du Narcisse (The Treatise of the Narcissus)

- Nothing is said that has not been said before. — Terence

The Immoralist (1902)

- Savoir se libérer n’est rien; l’ardu, c’est savoir être libre.

- Translation: To know how to free oneself is nothing; the arduous thing is to know what to do with one’s freedom.

- The Immoralist, Chapter 1 (1902)

Boléro

Before Boléro, Ravel had composed large scale ballets (such as Daphnis et Chloé, composed for the Ballets Russes 1909 – 1912), suites for the ballet (such as the second orchestral version of Ma mère l’oye, 1912), and one-movement dance pieces (such as La valse, 1906 – 1920). Apart from such compositions intended for a staged dance performance, Ravel had demonstrated an interest in composing re-styled dances, from his earliest successes, the 1895 Menuet and the 1899 Pavane, to his more mature works like Le tombeau de Couperin, which takes the format of a dance suite.

Boléro epitomises Ravel’s preoccupation with restyling and reinventing dance movements. It was also one of the last pieces he composed before illness forced him into retirement. The two piano concertos and the song cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée were the only completed compositions that followed Boléro.

Mac Tag

No Comments on "The Lovers’ Chronicle 22 November – with you – birth of George Eliot – art by Christian Rohlfs – premiere of Verdi’s La forza del destino – birth of André Gide – Maurice Ravel’s Boléro"